You are on CGS' Legacy Site.

Thank you for visiting CGS! You are currently using CGS' legacy site, which is no longer supported. For up-to-date information, including publications purchasing and meeting information, please visit cgsnet.org.

Featured

As a child, Joseph Taylor loved dinosaurs and wanted to be a paleontologist; but during his undergraduate work at Washington and Lee University, Taylor discovered his love for insects and spent three years researching the praying mantis.

After receiving his B.S. in biology with a minor in Russian language and culture, Taylor chose to continue his work as a doctoral student in entomology at Washington State University. Now he’s researching predator insects and their role in feeding on other insects that can potentially destroy crops. He hopes his research will lead to reduceduse of harmful broad spectrum pesticides in crops and build a healthier food supply for the world.

Taylor was recently awarded an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship and an Achievement Rewards for College Scientists to continue his work on predator insects. Once Taylor finishes his doctoral study, he hopes to work for the USDA on pest management. To learn more about Joseph and his research, visit the Washington State University website.

The CGS GRADIMPACT project draws from member examples to tell the larger story of graduate education. Our goal is to demonstrate the importance of graduate education not only to degree holders, but also to the communities where we live and work. Do you have a great story to share about the impact of master’s or doctoral education? Visit our WEBSITE for more information.

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

CONTACT: Julia Kent

202.461.3874 / jkent@cgs.nche.edu

Following is a statement by Council of Graduate Schools President Suzanne Ortega.

"In response to the March 6th Executive Order on Immigration, the Council of Graduate Schools (CGS) continues to affirm that our nation’s security is paramount and a strong visa process contributes to our safety. However, as an organization of approximately 500 universities, we also believe that the modified ban is still likely to have unintended consequences on U.S. graduate students and their institutions. Although this revision reduces the scope of the January 27th order, international graduate students and scholars, regardless of country of origin, may continue to view the uncertainty regarding visa policies as a deterrent to pursuing graduate studies in the United States."

"The strength of our nation’s graduate education depends upon both domestic and international talent. International faculty and students are vitally important to U.S. graduate education and research. They are essential contributors to our economy and research enterprise. International students (both graduate and undergraduate) contributed nearly $36 billion to the U.S. economy in 2014-15 (IIE, 2016). Domestic students benefit from the experience of training alongside international students, gaining the cultural competence needed to be competitive in a global economy. American graduate education represents the gold standard of higher education around the world, and we are committed to seeing it remain open to the best and brightest domestic and international talent."

###

The Council of Graduate Schools (CGS) is an organization of approximately 500 institutions of higher education in the United States and Canada engaged in graduate education, research, and the preparation of candidates for advanced degrees. The organization’s mission is to improve and advance graduate education, which it accomplishes through advocacy in the federal policy arena, research, and the development and dissemination of best practices.

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

Contact: Julia Kent | (202) 461-3874 / jkent@cgs.nche.edu

Declining Applications from Key Countries Contribute to Slowed Growth in Prospective Student Interest

Washington, DC —New data from the Council of Graduate Schools (CGS) reveal that first-time international graduate enrollment increased by 5% in Fall 2016, the same rate of growth seen last year. Yet U.S. institutions saw a lag in growth in the total number of international graduate applications, from 3% in 2015 to 1% in 2016.

The slow-down in application growth occurred despite a 4% increase in the number of applications from prospective Chinese graduate students, who constitute the largest subgroup of international students both in terms of applications and enrollments. The overall decrease in application growth was due to the combined effect of decreases in applications from important sending countries and regions: India (-1%), the Middle East and North Africa (-5%), South Korea (-5%), and Brazil (-11%).

While application counts of prospective European graduate students to U.S. institutions remained consistent with last year, first-time enrollment of European graduate students at U.S. institutions rose by 8%, ending the recent streak of declining enrollment growth rates from this region.

“The continued increase in enrollments is good news for U.S. universities,” said CGS President Suzanne Ortega, “but we can’t take that position for granted. Universities in the U.S. and around the world are waiting to see the potential impact of the uncertain policy environment on the mobility patterns of international graduate students.” Dr. Ortega added that the recent executive order that bars entry or return of U.S. visa holders from specific countries poses a concern. “We must ensure that the U.S. remains an attractive and viable place for the world’s most talented students to pursue education and research.”

The report also includes data on trends by field of study. In terms of total applications and first-time enrollments, Business (17% and 20% respectively), Engineering (30% and 26% respectively), and Mathematics and Computer Sciences (21% and 20% respectively) continue to be the most popular fields of study. Sixty-eight percent of total international graduate applications and 78% of first-time graduate enrollments were to master’s and certificate programs, suggesting that U.S. master’s programs continue to be viewed as good investments by international students.

As the only report of its kind to offer data on the current academic year, International Graduate Applications and Enrollment: Fall 2016 reports applications, admissions, and enrollments of international master’s, certificate, and doctoral students at U.S. colleges and universities. Additional report findings can be found in the attached page of highlights.

About the survey and report

Conducted since 2004, the CGS International Graduate Admissions Survey tracks the applications and enrollments of international students seeking U.S. master’s and doctoral degrees. In Fall 2016 the survey was redesigned to collect data by degree objective (master’s and graduate certificate vs. doctorate), and for all seven regions of origin, eight countries of origin, and all eleven broad fields of study, yielding the only degree-level data currently available for graduate admissions and enrollments. 395 U.S. graduate institutions who are members of CGS or its regional affiliates responded to the 2016 survey.

The Council of Graduate Schools (CGS) is an organization of approximately 500 institutions of higher education in the United States and Canada engaged in graduate education, research, and the preparation of candidates for advanced degrees. The organization’s mission is to improve and advance graduate education, which it accomplishes through advocacy in the federal policy arena, research, and the development and dissemination of best practices.

As a graduate student at Wayne State University, Jisha Panicker, B.D.S., M.P.H. worked as an intern with the Henry Ford Health System’s Women Inspired Neighborhood (WIN) Network: Detroit to improve women’s access to pre-natal healthcare and maternal support. Her local engagement produced award-winning research with direct impact on Detroit’s health services and the lives of women and families.

In Fall 2016, Panicker received the Public Health Education and Health Promotion (PHEHP) Student Award from the American Public Health Association (APHA) for her presentation: “Creating a sustainable group prenatal care model for the Women Inspired Neighborhood (WIN) Network: Detroit at the Henry Ford Health System.” She was one of ten top-ranked poster abstracts presented during the PHEHP section of the APHA Annual Meeting. Panicker's project sought to address the high infant mortality rate in Detroit despite its strong healthcare systems by creating a consortium of healthcare professionals in an enhanced group prenatal care (GPC) model.

Panicker graduated from Wayne State with her M.P.H. degree in October 2016. She also holds a bachelor’s degree in dental surgery and plans to, “address issues in oral health disparities and implement sustainable community-based disease prevention and health promotion strategies to promote affordable and accessible oral health care.” To learn more about Panicker and her research, visit the Wayne State University website.

The CGS GRADIMPACT project draws from member examples to tell the larger story of graduate education. Our goal is to demonstrate the importance of graduate education not only to degree holders, but also to the communities where we live and work. Do you have a great story to share about the impact of master’s or doctoral education? Visit our WEBSITE for more information.

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

CONTACT: Julia Kent

202.461.3874 / jkent@cgs.nche.edu

Following is a statement by Council of Graduate Schools President Suzanne Ortega.

"Our nation’s security is paramount and a strong visa process contributes to our safety. However, as an organization of approximately 500 universities, we encourage the administration to reconsider the executive order barring entry or return of individuals from specific countries."

"The strength of our nation’s graduate education depends upon both domestic and international talent. International faculty and students are vitally important to U.S. graduate education and research. They are essential contributors to our economy and research enterprise. International students (both graduate and undergraduate) contributed nearly $36 billion to the U.S. economy in 2014-15 (IIE, 2016). Domestic students benefit from the experience of training alongside international students, gaining the cultural competence needed to be competitive in a global economy. American graduate education represents the gold standard of higher education around the world, and we are committed to seeing it remain open to the best and brightest domestic and international talent."

###

The Council of Graduate Schools (CGS) is an organization of approximately 500 institutions of higher education in the United States and Canada engaged in graduate education, research, and the preparation of candidates for advanced degrees. The organization’s mission is to improve and advance graduate education, which it accomplishes through advocacy in the federal policy arena, research, and the development and dissemination of best practices.

By Linda DeAngelo

Some of the counselors there [at CSU attended] have real preconceived notions of what minority students are capable of achieving, and they steer minority students away from graduate school. They even went as far as to steer me away from being a math and science teacher. When I started at [CSU attended] they [counselors] wanted to place me in basic [remedial] courses and were really surprised by my test score.” Latina doctoral student studying biology. --From DeAngelo, 2009

He [a Latino student who had just as much potential as I do] did not have the information he needed to even really know what graduate school is all about or what it would take for him financially.

White doctoral student studying genetics. --From DeAngelo, 2009

Introduction

One of the most important influences to a student’s pursuit of graduate education—if not the most important—is having a faculty mentor during a student’s undergraduate education. This is especially relevant for students of color who remain underrepresented in graduate education (Kim, 2011; U.S. Department of Education, 2014). While there are a number of potential reasons for the underrepresentation of students of color in graduate education, one explanation that has gained traction, and is problematized in this brief, situates the problem as one of academic mismatch. Academic mismatch occurs when students are overmatched academically at the institutions they attend as undergraduates. Mismatch is thought to create a situation that causes overmatched students of color to perform poorly academically, which in turn limits their aspirations for and potential to succeed in graduate education. This narrative was recently argued in the Wall Street Journal opinion pages by law professor Gail Heriot of the University of San Diego, who discusses the reason why we do not have more black scientists. Heriot (2015) stated, “Encouraging black students to attend schools where their entering credentials places them at the bottom of the class has resulted in fewer black physicians, engineers, scientists, lawyers, and professors than would otherwise be the case.[1]” While academic achievement is relevant to graduate study, the research presented in this brief reveals that the real crisis is not academic mismatch but a scarcity of the mentoring relationships that lead to graduate education.

The brief begins with a review of mentoring – what constitutes mentoring, motivations for mentoring, which students get mentored, and the importance of mentoring to graduate education. A discussion of the scarcity of mentoring for students of color, especially at more selective institutions, and how this challenges the mismatch hypothesis follows. The brief concludes with ways that institutions can recognize barriers to faculty mentorship and support faculty in engaging in these relationships.

What Constitutes Mentoring and Motivations for Mentoring

Mentoring is described in a number of ways and can be constituted differently based on the relationship present. However, the most powerful mentoring relationships tend to encompass four characteristics. These characteristics include (a) a focus on achievement and development of potential, (b) a reciprocal and personal relationship, (c) a relationship where the mentor is an individual with more experience, influence, and achievement, and (d) a relationship where the mentor takes on emotional and psychological support and directly assists with career aspirations and planning through role modeling (Crisp & Cruz, 2009; Jacobi, 1991). These four characteristics move interaction between students and faculty to the level of mentoring.

Although expected roles for faculty include advising and teaching, which naturally includes interaction with students, the mentoring relationships that are most successful in supporting students to pursue graduate studies fall outside of this formal faculty role. For example, as DeAngelo and colleagues (2016) describe, expected role behavior with undergraduate students includes behavior that is aligned with institutional or departmental expectations of faculty role, such as advising regarding course selection and matriculation, the involvement of students in research experiences, and teaching of hard skills required for admission and success in graduate education. However, extra-role behavior that constitutes mentoring is behavior that is not explicitly required, recognized, or rewarded as part of faculty role (DeAngelo et al., 2016; Johnson & Ridley, 2004). This includes actively identifying and approaching students to initiate mentoring relationships, promoting graduate education as an option for students, and actively working to socialize students to the academic culture. In addition, this behavior takes place both within and outside formal channels, and the behavior within formal channels goes above and beyond the formally sanctioned role of the faculty.

Motivations to engage in this type of behavior vary, but for those within the DeAngelo and colleagues’ (2016) study, there were two primary reasons for engaging in these relationships. Some faculty pursued mentoring relationships with undergraduate students because of their personal experiences and a sense of responsibility related to assisting students to enter graduate study. For example, faculty discussed positive mentoring experiences that they wanted to emulate or a lack of mentorship they received that intensified their desire to mentor undergraduate students. Other faculty saw a benefit in supporting students with whom they could personally identify (students of color and/or first-generation students).

Who Gets Mentored and the Importance of Mentoring

Students who perform at high levels, and who demonstrate motivation and proactive behaviors, “rising stars” (Ragins & Cotton, 1999; Singh et al., 2009), fit the dominant paradigm for student success (Bensimon, 2007), and are more likely to be mentored (Fuentes, et al., 2014; Robertson, 2010). In this dominant paradigm for student success, “the student is an autonomous and self-motivated actor who exerts effort in behaviors that exemplify commitment, engagement, regulation, and goal-orientation” (Bensimon, 2007, p. 447). Therefore, “rising stars” tend to be more engaged in their academic endeavors and interact informally with faculty during their early college careers. Fuentes and colleagues (2014) demonstrate that this early interaction with faculty results in more frequent mentoring relationships later in college. The lack of investment in mentoring students that faculty initially identify as “lesser quality” works against diversification of graduate education.

While mentoring relationships can be initiated by either party and can take shape in a number of ways, the most meaningful mentoring relationships emerge when there is a commitment by both the student and faculty member. These active and committed relationships help students become oriented to their institutions and their academic fields (Becher, 1989; Eagan et al., 2011; Weidman, 2006) and provide valuable networking resources and access to information (Stanton-Salazar, 1997, 2010). Especially important to increasing diversity in graduate studies, strong mentoring relationships guide students along their educational pathways, helping them to gain additional confidence to pursue advanced studies (Crisp & Cruz, 2009; DeAngelo, 2009, 2010; Eagan et al., 2011; Landefeld, 2009; Seymour et al., 2004).

Research demonstrates that students of color have degree aspirations that equal or exceed their white counterparts, yet they are no more likely than white students to pursue graduate study (Cherwitz, 2013; English & Umbach, 2016). Students of color are also less likely to be mentored than white students (Felder, 2010; Johnson, 2015; Milkman et al., 2014, Thomas et al., 2007). Even though students of color are less likely to be mentored, studies continue to document the importance of these relationships for pursuing graduate education. Faculty mentors can serve as role models within the discipline and provide cultural and social capital for diverse students, especially in fields where women and minorities are particularly underrepresented (Whittaker & Montgomery, 2014). While beneficial to all students, intensive mentoring relationships may be particularly important for students of color in pursuing graduation study (Davis, 2008; Davidson & Foster-Johnson, 2001; DeAngelo, 2009, 2010; Felder, 2010).

Examining the Mentoring Crisis for Student of Color at Selective Institutions

In examining faculty mentorship for students of color, the study of DeAngelo (2008) is particularly relevant and will be explored in some detail here. This study examined the role of the college experience in the development and maintenance of PhD degree aspirations[2]. To understand the role of institutional selectivity as it relates to the opportunity for mentorship, it is important to first examine relationships as the relate distribution of students by selectivity. From the DeAngelo (2008) study, Table 1 displays the distribution of underrepresented racial minority[3] and white students by institutional selectivity in the study and Table 2 displays these relationships restricted to just those students who aspire to the PhD at the end of college.

Table 1:

|

Distribution of Students by Institutional Selectivity in Full Sample from DeAngelo (2008) Study |

|||

|

|

Low Selectivity |

Medium Selectivity |

High Selectivity |

|

White |

32% |

36% |

32% |

|

Underrepresented Racial Minority |

40% |

28% |

32% |

Table 1 shows that an equal percentage of underrepresented racial minority students and white students attend high selectivity institutions (32%), but a disproportionate percentage of underrepresented racial students attend low selectivity institutions (40% in comparison to 32% of white students). These relationships as they relate selectivity change dramatically when the sample of undergraduate students is restricted to those who aspire to the PhD at the end of college. Table 2 shows that among white students at low selectivity institutions a smaller percentage (25%) than in the overall sample (32% Table 1) aspire to the PhD at the end of college, whereas at high selectivity institutions the percentage of white students (41%) is higher than in the overall sample (32% Table 1). For white students, as selectivity increases so does the percentage who aspire to the PhD at the end of college. A much different relationship is present for underrepresented racial minority students. At low selectivity institutions the percentage of underrepresented racial minority students who aspire to the PhD at the end of college is roughly the same (39%) as in the overall sample (40% Table 1). Further, at high selectivity institutions while the percentage of underrepresented racial minority students who aspire to the PhD at the end of college is higher (36%) than the percentage in the overall sample (32% Table 1) the percentage point increase is not nearly as large as it is for white students (4 vs 9 percentage points). The question then becomes what contributes to these relationships? The weight of the evidence in the results from the DeAngelo (2008) study demonstrates that access to mentoring rather than academic mismatch underlies these differences[4].

Table 2:

|

Distribution of Students by Institutional Selectivity Restricted to Students Who Aspire to the PhD at the End of College from DeAngelo (2008) Study |

|||

|

|

Low Selectivity |

Medium Selectivity |

High Selectivity |

|

White |

25% |

34% |

41% |

|

Underrepresented Racial Minority |

39% |

25% |

36% |

In looking at the results from the DeAngelo (2008) study, the single largest effect on PhD aspirations was the level of faculty encouragement for graduate study. The higher the amount of encouragement for graduate study from faculty, the more likely both underrepresented racial minority students and white students were to aspire to the PhD (all other factors equal and controlled). Although both white students and underrepresented racial minority students benefited from encouragement for graduate study, a factor that is part of a strong mentoring relationship for students of color (DeAngelo, 2009; 2010), the relative size of the benefit was much larger for underrepresented racial minority students. Odds ratios from the study indicate that occasional encouragement for graduate study (vs. no encouragement) increases the odds of a white student aspiring to the PhD at the end of college by 42%, whereas the increase in odds is 238% for underrepresented racial minority students. At the frequent encouragement level (vs. no encouragement) the trend continues with white students having a 170% larger odds of aspiring to the PhD and underrepresented racial minority students having a 332% increased likelihood of PhD aspirations.

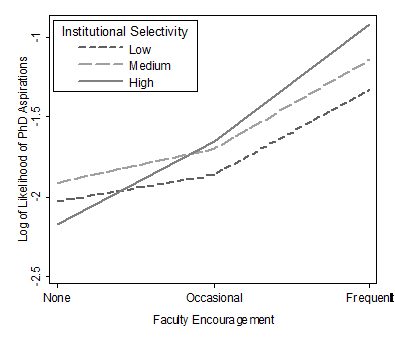

Returning to the role of institutional selectivity in access to faculty mentoring, the DeAngelo (2008) study tested for an interaction effect between selectivity and faculty encouragement. For white students, this interaction was significant (see Figure 1). In this figure, the level of encouragement a white student receives is on the X axis and the log likelihood increase in PhD aspirations is on the Y axis. The dotted and solid lines graph the increases in PhD aspirations by institutional selectivity (low, medium, high) and encouragement level. As the figure demonstrates, white students who are encouraged frequently are more likely to aspire to the PhD at the end of college if they are at a high selectivity institution, and less likely if they are at a low selectivity institution (all other factors equal, and controlled). Further, additional testing demonstrated that the difference in odds is significantly different at low and high selectivity institutions, an increase in odds of 52% for frequent encouragement and high vs. low selectivity, and a decrease in odds of 13% for no encouragement and high vs. low selectivity. Thus, white students who attend high selectivity institutions who are not encouraged for graduate study are significantly less likely to aspire to the PhD at the end of college than are equally similar white students who attend low selectivity institutions. This finding suggests that in the absence of faculty encouragement at high selectivity institutions white students have difficulty envisioning themselves as a future member of professoriate.

Figure 1: Interaction between Selectivity and Faculty Encouragement for Graduate Study for White Students from the DeAngelo (2008) Study

The DeAngelo (2008) study ran the same interaction for underrepresented racial minority students and the effect was not significant. Specifically, results in the study demonstrated that differences in the significance of this interaction for white and underrepresented racial minority students were likely related to the chances of being encouraged for graduate study by institutional selectivity. Keeping in mind faculty encouragement is a strong factor in PhD aspirations in this study, and that faculty mentoring is particularly important to graduate study for student of color (Davis, 2008; Davidson & Foster-Johnson, 2001; DeAngelo, 2009, 2010; Felder, 2010), data from this study indicated that white students were just as likely to be frequently encouraged for graduate study at high (35%) and low selectivity institutions (36%), whereas underrepresented students were more likely frequently encouraged at low (55%) vs. high selectivity institutions (40%). Thus, the weight of evidence in DeAngelo (2008) study suggests that it is the opportunity for encouragement at high and low selectivity institutions[5] for underrepresented racial minority students, rather than academic mismatch which is depressing aspirations for the PhD at high selectivity institutions and contributing to the lack of diversity present in graduate study, the pipeline to the professoriate and learned professions.

Barriers and Supports to Mentoring

In order to increase the opportunity for students of color to be mentored, institutional leaders and those concerned about diversity in graduate education must support mentoring. The DeAngelo and colleagues (2016) study identified that barriers and supports to mentoring typically fit within three areas: the culture of the institution, the culture of the academic discipline, or the culture of the academic profession. The culture of the institution either promotes or deters mentoring in a number of ways. For example, the institutional expectations related to teaching and advising can hinder the development of mentoring relationships, the educational mission can impede engagement in mentoring toward graduate study, and institutional support for graduate study can be relegated to a few programs that do not serve many students. Conversely, institutional culture can support the development of mentoring by creating settings where a group of faculty can be jointly committed to promoting mentoring and graduate study. These settings created cultural supports for mentoring despite an overall cultural ethos at the institution that was a deterrent. Ultimately, without a supportive institutional culture, DeAngelo and colleagues (2016) concluded that faculty members who wish to engage in mentoring must, in general, work against that overall institutional culture.

Secondly, DeAngelo and colleagues (2016) found that academic discipline can promote or deter mentoring behaviors. Sixty-one percent of STEM faculty compared to 18% of Humanities and Social Science faculty in the study discussed research experiences as a way to engage with students. This platform is naturally available to STEM disciplines where research labs provide a structure to facilitate interaction and opportunities for mentoring relationship to develop. Conversely, humanities and social science disciplines must work to use the classroom to engage students, where mentoring behavior may take additional effort to manifest.

Finally, the culture of the academic profession creates a host of barriers and few, if any, supports to mentoring behaviors. The culture of the academic profession regulates the availability of opportunities for extra-role behavior through a system of promotion and tenure that drives the importance and need for research productivity and lacks rewards for mentoring undergraduates or a recognition of the time it takes to engaging in mentoring students. Lastly, in the DeAngelo and colleagues study (2016), the faculty workload related to teaching can lead faculty to overly focus on teaching as interaction, which can become a substitute for mentoring.

Shifting Culture to Support Mentoring

Given the importance of mentoring to access to graduate study, especially for underrepresented racial minority students, it is imperative that institutional leaders support the extra-role behaviors associated with developing these positive relationships. Specifically, we need to address the bias, racialized and otherwise, engrained in institutional cultures that have resulted in this crisis of mentoring of students of color at selective institutions. Shifting these cultures requires institutional leaders and other institutional actors to interrupt the oppressive structures that allow the bias inherent in these cultures to silently propagate limiting beliefs regarding the academic capacity students of color who attend these institutions[6].

Moreover, individual actors and institutional leaders need to actively and demonstrably value faculty engagement in mentorship. Incorporating mentorship as a critical component of quality undergraduate education (DeAngelo et al., 2016) remains a vital first step in building cultures that supports mentoring. Overt communication from institutional leaders that emphasizes the necessity of faculty mentorship for undergraduate students in the creation of the next generation of faculty and a diverse professoriate serves as another foundational component of structurally supporting mentorship. Recognizing the time intensive nature and workload associated with mentoring and incorporating it into how faculty are rewarded externally validates this behavior and contributes to shifting culture. Only when we have the cultural shifts that produce equity as it relates who is mentored toward graduate education can we realize the potential to develop a diverse pipeline into the professoriate and learned professions.

Note: This brief is based on a presentation given at the Spring 2016 CGS Research & Policy Forum. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Council of Graduate Schools.

Suggested Citation: DeAngelo, L. (2016). Supporting Students of Color on the Pathway to Graduate Education (CGS Data Sources PLUS 16-02). Washington, DC: Council of Graduate Schools.

About the Author: Linda DeAngelo is assistant professor of higher education and Center for Urban Education Faculty Fellow at the University of Pittsburgh. Email: deangelo@pitt.edu.

References

Arcidiacono, P., & Lovenheim, M. (2016). Affirmative action and the quality-fit tradeoff. Journal of Economic Literature. 54 (1): 30, 31 and 69. doi:10.1257/jel.54.1.3.

Becher, T. (1989). Historians on history. Studies in Higher Education, 14(3), 263-278.

Bensimon, E. M. (2007). The underestimated significance of practitioner knowledge in the scholarship on student success. The Review of Higher Education, 30(4), 441-469.

Cherwitz, R. A. (2013). The challenge of diversifying higher education in the post-fisher era: No profound increase in diversity will occur until significant and progress is made in convincing talented minorities to pursue graduate study. Planning for Higher Education, 41(1), 113-116.

Cole, S., & Barber, E. (2003). Increasing faculty diversity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Crisp, G., & Cruz, I. (2009). Mentoring college students: A critical review of the literature between 1990 and 2007. Research in Higher Education, 50, 525–545. doi:10.1007/s11162-009-9130-2.

Davidson, M., & Foster-Johnson, L. (2001). Mentoring in the preparation of graduate researchers of color. Review of Educational Research, 71(4), 549–574.

Davis, D. J. (2008). Mentorship and the socialization of underrepresented minorities into the professoriate: examining varied influences. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 16(3), 278–293.

Davis, J. A. (1966). The campus as a frog-pond: an application of the theory of relative deprivation to career decisions of college men. American Journal of Sociology, 72(1), 17-31.

DeAngelo, L. (2008). Increasing faculty diversity: How institutions matter to the PhD aspirations of undergraduate students (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. (Accession Order No. AAT 3302576).

DeAngelo, L. (2009). Can I go?: An exploration of the influence of attending a less selective institution on students’ aspirations and preparation for the Ph.D. In M. F. Howard-Hamilton, C. L. Morelon-Quainoo, S. D. Johnson, R. Winkle-Wagner, & L. Santiague (Eds.), Standing on the outside looking in: Underrepresented students’ experiences in advanced degree programs (pp. 25-44). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

DeAngelo, L. (2010). Preparing for the PhD at a comprehensive institution: Perceptions of the “barriers.” Journal of the Professoriate, 3(2), 17-49.

DeAngelo, L., Mason, J., & Winters, D. (2016). Faculty engagement in mentoring undergraduate students: How institutional environments regulate and promote extra-role behavior. Innovative Higher Education, 41:317–332. doi: 10.1007/s10755-015-9350-7.

Eagan, K., Herrera, F. A., Garibay, J. C., Hurtado, S., & Chang, M. (2011, May). Becoming STEM proteges: Factors predicting the access and development of meaningful faculty-student relationships. Paper presented at the Association for Institutional Research Annual Forum, Toronto.

English, D., & Umbach, P. D. (2016). Graduate school choice: An examination of individual and institutional effects. Review of Higher Education, 39(2), 173-211.

Felder, P. (2010). On doctoral student development: Exploring faculty mentoring in the shaping of African American doctoral student success. Qualitative Report, 15(2), 455–474.

Fuentes, M., Berdan, J., Ruiz, A., & DeAngelo, L. (2014). Mentorship matters: Does early faculty contact lead to quality faculty interaction? Research in Higher Education, 55, 288-307. doi: 10.1007/s11162-013-9307-6.

Heriot, G. (2015, October 21). Why aren’t there more black scientists? The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from www.wsj.com.

Jacobi, M. (1991). Mentoring and undergraduate academic success: A literature review. Review of Educational Research, 61(4), 505–532.

Johnson, W., & Ridley, C. (2004). The elements of mentoring. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Johnson, W. B. (2015). On being a mentor: A guide for higher education faculty. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kim, Y. M. (2011). Minorities in higher education: Twenty-fourth status report, 2011 Supplement. Washington, D.C.: American Council on Education.

Landefeld, T. (2009). Mentoring and diversity: Tips for students and professionals for developing and maintaining a diverse scientific community. New York, NY: Springer.

Milkman, K. L., Akinola, M., Chugh, D. (2014). What happens before? A field experiment exploring how pay and representation differentially shape bias on the pathway into organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(6), 1678-1712. doi:10.1037/ap10000022

McCoy, D. L., Winkle-Wagner, R., & Luedke, C. L. (2015). Colorblind mentoring? Exploring white faculty mentoring of students of color. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 8(4), 225–242. doi:10.1037/a0038676

Ragins, B. R., & Cotton, J. L. (1999). Mentor functions and outcomes: A comparison of men and women in formal and informal mentoring relationships. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 529–550.

Robertson, T. M. A. (2010). Making the connection: How faculty choose proteges in academic mentoring relationships (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest Dissertation and Theses (Accession No. 3417777).

Sander, R. H. (2004). A systemic analysis of affirmative action in American law schools. Stanford Law Review, 57(2), 367-483.

Seymour, E., Hunter, A., Laursen, S. L., & DeAntoni, T. (2004). Establishing the benefits of research experiences for undergraduates in the sciences: First findings from a three-year study. Science Education, 88, 493–534.

Singh, R., Ragins, B. R., & Tharenou, P. (2009). Who gets a mentor? A longitudinal assessment of the rising star hypothesis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(1), 11–17.

Stanton-Salazar, R. D. (1997). A social capital framework for understanding the socialization of racial minority children and youths. Harvard Educational Review, 67(1), 1-41.

Stanton-Salazar, R. D. (2010). A social capital framework for the study of institutional agents and their role in the empowerment of low-status students and youth. Youth & Society. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/0044118X10382877.

Thomas, K. M., Willis, L. A., & Davis, J. (2007). Mentoring minority graduate students: Issues and strategies for institutions, faculty, and students. Equal Opportunities Interactions, 26(3), 178-192. DOI 10.1108/02610150710735471

U.S. Department of Education (2014). Postsecondary completers and completions: 2011-12. Washington D.C.: National Center for Education Statistics.

Weidman, J. (2006). Student socialization in higher education: Organizational perspectives. In C. Conrad & R. C. Serlin (Eds.), The SAGE handbook for research in education: Engaging ideas and enriching inquiry (pp. 253-262). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Whittaker, J. A., & Montgomery, B. L. (2013). Cultivating institutional transformation and sustainable stem diversity in higher education through integrative faculty development. Innovative Higher Education, 39(4), 263–275.

[1] See Cole & Barber (2003), Saunder (2004), and Arcidiacono & Lovenheim, (2016) for scholarly examinations of the mismatch hypothesis, and Davis (1966) for the social theory of mismatch, also termed the frog-pond hypothesis. Arguments related to mismatch suggest that if students of color attended institutions where there entering credentials were better matched, their academic performance would be stronger and more would then aspire to and successfully enter graduate education, the pipeline to the professoriate and learned professions.

[2] The DeAngelo (2008) study used hierarchical generalized linear modeling to study PhD aspirations development at the end of the college experience for underrepresented racial minority and white students. The study included 13,645 students at 251 institutions across the country.

[3] In the DeAngelo (2008) study the term underrepresented racial minority students was used to refer to Black/African American, Hispanic/Latinx, and American Indian students which were the focus of the study. In this brief this term is used specifically when the results of the DeAngelo (2008) study are discussed; whereas the term students of color is used throughout the rest of the brief.

[4] A direct test of the mismatch hypothesis (Davis, 1966) was conducted in the DeAngelo (2008) study. Results indicated that there was no evidence of mismatch for underrepresented racial minority students as it contributed to PhD aspirations.

[5] In the DeAngelo (2008) study at the institutional level selectivity was a significant predictor of PhD aspirations for both underrepresented racial minority and white students.

[6] See McCoy, Winkle-Wagner, Luedke (2015) for an empirical exploration of this issue.

As the first legally blind person to earn a doctorate in genetics from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and possibly only the second blind UW–Madison Ph.D. in biological sciences, Dr. Andrew (Drew) Hasley wants to improve biological education so future students with disabilities can succeed in whatever field they choose.

Hasley started his first biology research job as an undergraduate at Albion College in Michigan and continuing his study in graduate school seemed an obvious next step. His dissertation research blends statistical and computational analyses of large datasets with techniques from developmental and molecular biology to answer basic biological questions about the early development of vertebrate embryos, using zebrafish as a model.

Hasley is currently a postdoctoral fellow in the Pelegri Lab at UW-Madison and looking for his next opportunity. “Whatever it is must involve teaching,” Hasley says. “I see an opportunity to improve biological education in a way that will get more people into it who are like me. There is no reason for me to be this rare.” To learn more about Hasley and his research, visit the UW-Madison website.

The CGS GradImpact project draws from member examples to tell the larger story of graduate education. Our goal is to demonstrate the importance of graduate education not only to degree holders, but also to the communities where we live and work. Do you have a great story to share about the impact of master’s or doctoral education? Visit our website for more information.

**Please note: CGS will only feature stories from CGS member institutions, but we welcome the use of #GradImpact by the larger graduate and professional education community to promote this important work.

Join CGS in Advocating for the Power of Graduate Education

Do you have a great story to share about the impact of master’s or doctoral education? Do you know a graduate student or alumnus whose work has the potential to cure a disease, alleviate poverty, or educate the public? The Council of Graduate Schools would like to hear from you.

CGS will draw from member examples to tell the larger story of graduate education through a variety of outlets: the CGS website, newsletters, social media, advocacy efforts, and media outreach. Our goal is to demonstrate that graduate education matters not only to degree holders, but also to the communities where they live and work.

To that end, we invite CGS member institutions to submit stories in one of three categories below.*

- Innovative Graduate Students

Tell us about a current master’s or doctoral student who is engaged in innovative, high-impact research and/or professional activity. Examples might include, but not be limited to, a doctoral student conducting cutting-edge research, a PMA or PSM student advancing the work of a company or non-profit organization, or a group of MBA students who have created a promising start-up company.

- Recent Alumni Making a Difference

Highlight a recent alum or alums (graduating between 2011 and 2016) who has used their graduate education to make a difference. Examples might be alums working to improve public health locally or globally, educating and inspiring the public in a museum or library, doing high-impact research at a university or national laboratory, or improving teaching and learning.

- Exceptional Employers

Tell us about an employer of graduate students or alumni who is making a difference in the business, non-profit or government sectors. Examples might include employers working to bring medications to market more quickly and safely, to inform public policies, or to bring the arts to a public school system.

Criteria for Selection of Stories:

A committee will evaluate our selection of stories using the following principles:

- Impact on the Public Good: We are seeking examples that positively impact (or have a high potential to impact) the lives of others through education, health, safety and security, the humanities, and economic development. Examples from any field of study are welcome.

- Diversity: CGS will seek to present a diverse range of member institutions, fields of study, and degree types. We also seek a diverse representation of participants in graduate education, particularly in terms of race/ethnicity, gender, and age.

- Share-ability: We will give priority to examples that are already available publicly on at least one website. This will allow us to share them more broadly through our own website and social media outlets. For this reason, we require submissions to include a link to a URL address.

Stories deemed to be particularly effective at demonstrating the impact of graduate education on the public good will be highlighted on the home page of the CGS website or in GradEdge.

*There is no limit on the number of stories your institution may submit. However, please be aware that a large number of submissions will not result in greater representation of your institution in CGS outlets. We will work to ensure that representation is evenly distributed among member institutions that choose to submit examples.

Instructions for Submitting Stories:

Please complete this electronic web form.

Contact:

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE:

October 27, 2016

Contact

Katherine Hazelrigg (202) 461-3888/ khazelrigg@cgs.nche.edu

Washington, D.C. — The Council of Graduate Schools (CGS) announced today that it has been awarded a grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation to help universities collect data on the career pathways of humanities PhDs. Through a competitive sub-award process, CGS will select 15 doctoral institutions to pilot surveys of humanities PhD students and alumni, gathering information about their professional aspirations, career pathways, and career preparation.

The project builds upon two earlier phases of CGS research: a feasibility study supported by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and a survey development phase supported by Mellon, Sloan, and the National Science Foundation (NSF). In the most recent phase, CGS developed two surveys—one for current PhD students and one for PhD alumni— by gathering input from senior university leaders, research funders, disciplinary societies, researchers, PhD students, and alumni.

While recent data exist on the first jobs obtained by PhDs in the humanities, relatively little is known about the longer career trajectories of these degree-holders. The survey pilot will be the first large-scale effort to collect data on the long-term career pathways of humanities PhDs since 1996, when the National Science Foundation’s Survey of Doctoral Recipients (SDR) eliminated the humanities from its data-collection efforts. While the main purpose of the project is to enable institutions to collect data about their own PhD alumni, it will also provide an opportunity to analyze patterns across the 15 partner institutions.

CGS President Suzanne Ortega noted that the initiative has the potential to improve the preparation of humanities PhDs for a more diverse range of careers. “Information on the full range of careers that humanities PhDs follow will allow graduate schools to improve curricula, professional development opportunities and career counseling services,” she said. “By offering a more complete picture of PhD holders’ career options, it will also enable current and prospective students to make more informed decisions when selecting degree programs and planning their careers.”

In the coming months, CGS will issue a Request-For-Proposals (RFP) to CGS member institutions to participate in the project as funded partners. The RFP will be accompanied by the survey instruments and an Implementation Guide that offers a framework for successful implementation. In addition to collecting aggregate data from partners, CGS will gather information about the implementation process with a view to developing recommended practices for data collection and analysis.

CGS’s career tracking project will complement its recently-announced effort to support career diversity for humanities PhDs. Through a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), CGS has established the Next Generation Humanities PhD Consortium (Next Gen Consortium), a collaborative learning community for the 28 NEH Next Generation PhD grant awardees. These universities, all of which are CGS member institutions, will seek to broaden the career preparation of PhD students in the humanities.

About CGS

The Council of Graduate Schools (CGS) is an organization of approximately 500 institutions of higher education in the United States and Canada engaged in graduate education, research, and the preparation of candidates for advanced degrees. The organization’s mission is to improve and advance graduate education, which it accomplishes through advocacy in the federal policy arena, research, and the development and dissemination of best practices.

About the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation

Founded in 1969, The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation endeavors to strengthen, promote, and, where necessary, defend the contributions of the humanities and the arts to human flourishing and to the well-being of diverse and democratic societies by supporting exemplary institutions of higher education and culture as they renew and provide access to an invaluable heritage of ambitious, path-breaking work. Additional information is available at mellon.org.

In 2016, CGS received a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) to establish the Next Generation Humanities PhD Consortium (Next Gen Consortium), a collaborative learning community for the 28 NEH Next Generation PhD grant awardees. These universities, all of which are CGS member institutions, seek to strengthen the career preparation of PhD students in the humanities. CGS provided intellectual leadership to this group and guided their mission to transform the culture of graduate education.

New resource: Inclusive language options for talking about humanities PhD careers

Other results from the project include:

Written to help guide applicants to NEH Next Generation Humanities PhD grants, as well as any campus team interested in pursuing the goals of the Next Gen program. Part I, Lessons Learned, summarizes the common features of Next Gen projects and outlines some of the challenges and promising solutions employed by grantee universities in pursuit of the larger goals of the grant program. Part II, Emerging Strategies, offers suggestions for additional considerations that might be included in the design of Next Gen programs. Please note that Promising Practices does not constitute evaluation criteria for the selection of 2018 grantees; rather, this document is intended to help institutions understand what practices have been most successful for past grantees, and identify ideas and approaches that are appropriate to their campuses.

Provides a history of prior work in humanities PhD professional development, and is intended to serve as an introduction to the field for anyone interested in professional development for humanities PhDs.

Contact