You are on CGS' Legacy Site.

Thank you for visiting CGS! You are currently using CGS' legacy site, which is no longer supported. For up-to-date information, including publications purchasing and meeting information, please visit cgsnet.org.

General Content

The University as Mentor: Lessons Learned from UMBC Inclusiveness Initiatives

The University as Mentor outlines the key actions that the University of Maryland Baltimore County has taken to achieve an inclusive graduate community. Recognizing that universities face common challenges and often benefit from the shared lessons of others, this case study presents ten “lessons learned” and practical advice intended to be accessible and applicable to other universities. The “lessons learned” identified here address two national challenges facing graduate education. First, the recruitment challenge is answered by describing the steps that must be taken to create a welcoming and positive environment for underrepresented students, an environment that will attract and support doctoral students throughout their academic careers and position them to be successful in the job market. Second, the retention challenge is addressed by describing how research universities can change their institutional environment in ways that promote success among its doctoral students, paying particular attention to fostering degree completion of underrepresented minorities and women. This publication builds not only on the UMBC experience, but also on important research and publications on the topics of doctoral student attrition, retention and mentoring.

To download the complete case study, please please click here (PDF).

Contents:

- Front Matter (PDF)

- Introduction

- Lesson One - Campus Leadership

- Lesson Two - Campus-wide Involvement

- Lesson Three - Graduate Admissions

- Lesson Four - Mentoring Systems

- Lesson Five - Monitoring Graduate Student Progress

- Lesson Six - Orientation

- Lesson Seven - Financial Support

- Lesson Eight - Recognition and Rewards

- Lesson Nine - Support Systems for Underrepresented Students

- Lesson Ten - Professional Development

- Conclusion

Preferred Citation: Scott A. Bass, Janet C. Rutledge, Elizabeth B. Douglass, Wendy Y. Carter. (2007). Lessons Learned: Shepherding Doctoral Students to Degree Completion. Washington, DC: Council of Graduate Schools.

Copyright: 2007 UMBC, Baltimore, Maryland and Council of Graduate Schools, Washington, DC.

CGS publishes reports, best practice volumes, and flyers that specifically address international issues in graduate education and topics of global scope.

Graduate Education for Global Career Pathways

This proceedings volume of the Sixth Annual Strategic Leaders Global Summit on Graduate Education offers new strategies for communicating the value of global careers across campus and examples of programs designed to equip graduate students with “global” skills.

Global Perspectives on Career Outcomes for Graduate Students: Tracking and Building Pathways (2012)

Global Perspectives on Career Outcomes for Graduate Students: Tracking and Building Pathways (2012)

The proceedings of the 2011 Global Summit on Graduate Education presents strategies for tracking graduate student employment, exposing students to career pathways inside and outside academe, and supporting the development of professional and transferable skills.

Global Perspectives on Measuring Quality (2011)

Global Perspectives on Measuring Quality (2011)

The proceedings of the 2010 Strategic Leaders Global Summit examines the benefits and challenges of assessing the quality of master's and doctoral programs in different global regions while highlighting international best practices in measuring quality.

Graduate Study in the United States (2011)

Graduate Study in the United States (2011)

This flyer provides practical advice for international students considering applying to graduate school in the US. Includes basic information about academic and professional degree types, typical requirements, selecting a program, preparing for graduate study and applying, the admissions decision process, student visas, and funding options. Includes a graduate application checklist.

This publication reviews what we currently know about graduate international collaborations, the gaps in our understanding, and what areas call for greater clarification. Includes case studies and a checklist for international MOU’s.

Global Perspectives on Graduate International Collaborations (2010)

Global Perspectives on Graduate International Collaborations (2010)

The proceedings of the 2009 Strategic Leaders Global Summit features essays, summaries of the dynamic discussions that took place at the summit, and a set of international guidelines agreed upon by summit participants, "Principles and Practices for Developing Effective International Collaborations."

Global Perspectives on Research Ethics and Scholarly Integrity (2009)

Global Perspectives on Research Ethics and Scholarly Integrity (2009)

The proceedings volume of the 2009 Strategic Leaders Global Summit identifies exciting opportunities for international collaboration around issues of research ethics.

Global Perspectives on Graduate Education (2008)

Global Perspectives on Graduate Education (2008)

This publication features essays and discussions from the inaugural Strategic Leaders Global Summit in 2007. The book identifies shared concerns about the challenges of a rapidly changing global environment and approaches to addressing those challenges.

Graduate Study in the United States: A Guide for Prospective International Graduate Students (2007

)

Graduate Study in the United States: A Guide for Prospective International Graduate Students (2007

)

This publication offers a clear and concise overview of the essential information all international students need in order to prepare for graduate study in the United States.

Career Outcomes for Graduate Students: Tracking and Building Pathways

Hong Kong

Increasingly, graduate institutions from around the world are seeking to enhance the professional skills and career outcomes of Master’s and PhD students. Many stakeholders join them in their efforts: national and provincial governments are working to strengthen the link between graduate training and workforce development, and international and local employers are joining national conversations about transferable skills and workforce needs. Most importantly, graduate students in many countries are asking for improved information and support for their career development both inside and outside academe.

These parallel trends have led graduate deans and other senior university leaders to closely follow workforce trends both locally and globally. Many universities have also sought to develop better methods of tracking graduates’ career pathways and to develop programs that prepare students to adapt to new and evolving career demands.

Co-convened by CGS and The University of Hong Kong (HKU), the Fifth Annual Strategic Leaders Global Summit on Graduate Education provided an international forum for exploring these efforts and exchanging best practices.

Event Materials:

- Press Release

- Principles and Practices for Building Pathways from Graduate School to Careers (PDF)

- Global Perspectives on Career Outcomes for Graduate Students: Tracking and Building Pathways

CGS contributions to the 2011 Summit were supported by a generous gift from ProQuest.

(Reprinted from the January/February 2011 issue of the CGS Communicator)

Hispanic-serving institutions (HSIs) play an important role in graduate education. According to the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities (HACU), HSIs are defined as “…colleges, universities, or systems/districts where total Hispanic enrollment constitutes a minimum of 25% of the total enrollment. ‘Total Enrollment’ includes full-time and part-time students at the undergraduate or graduate level… (Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities, 2011).” The federal government does not maintain an official list of HSIs, but as of January 2011, HACU listed 230 member HSIs on its website. Of those institutions, 53 award graduate degrees and are included in the survey population for the CGS/GRE Survey of Graduate Enrollment and Degrees. It is important to note that since the enrollment share of Hispanic students at individual institutions varies from year to year, the list of institutions considered HSIs also varies from year to year. This article examines graduate enrollment at institutions classified as HSIs by HACU as of January 2011.

Findings

The Hispanic population in the United States has increased rapidly over the past two decades. Hispanics comprise about 16% of the U.S. resident population today, up from about 13% in 2000 and 9% in 1990 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2000, 2002, and 2008). The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that by 2050, 30% of all U.S. residents will be Hispanic (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008).

Partly as a result of this population growth, the participation of Hispanics in graduate education has increased as well. In fall 2009, 8.4% of all U.S. citizen and permanent resident graduate students were Hispanic, up from 6.7% in 1999 and 3.9% in 1989 (Council of Graduate Schools, 2010). Yet, Hispanics remain underrepresented in graduate education. Their share of the U.S. population today is twice as large as their share of U.S. citizen and permanent resident graduate enrollment.

In fall 2009, 36% of all Hispanic graduate students attended HSIs, relatively unchanged from 37% a decade earlier in fall 1999 (Council of Graduate Schools, 2010). However, Hispanic graduate students are less likely to be enrolled at HSIs today than they were twenty years ago. In fall 1989, 44% of all Hispanic graduate students were enrolled at institutions now classified as HSIs. Despite a smaller share of Hispanics attending HSIs today, the large increase in Hispanic graduate enrollment over the past two decades has resulted in larger numbers of Hispanics at both HSIs and non-HSIs.

On average, graduate students at HSIs are more likely to be enrolled at the master’s level than students at non-HSIs. In fall 2009, 85% of all graduate students attending HSIs were enrolled at the master’s level compared with 75% of the graduate students at all other institutions (Council of Graduate Schools, 2010).

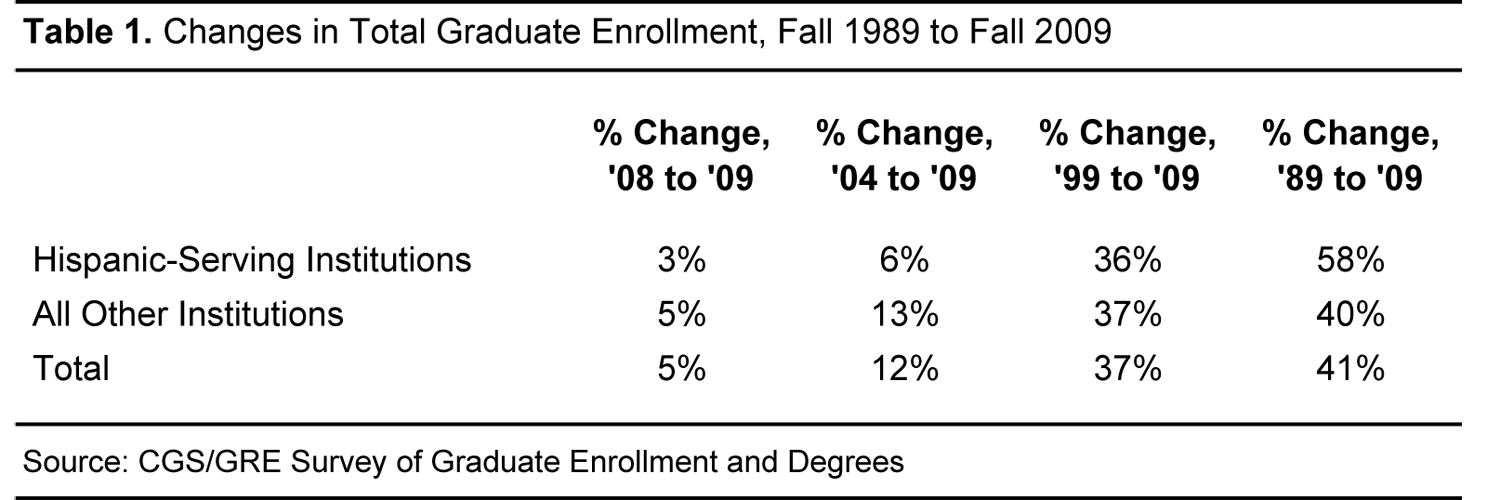

Over the past twenty years, the overall growth in graduate enrollment (including students of all citizenships and races/ethnicities) has been greater at HSIs than at all other institutions (see Table 1). Between fall 1989 and fall 2009, total graduate enrollment increased 58% at HSIs and 40% at all other institutions (Council of Graduate Schools, 2010). In contrast, over the last one-, five-, and ten-year periods, the gains were greater at non-HSIs than at HSIs. For example, between fall 2004 and fall 2009, total graduate enrollment increased 6% at HSIs, less than half the 13% rate of increase at all other institutions.

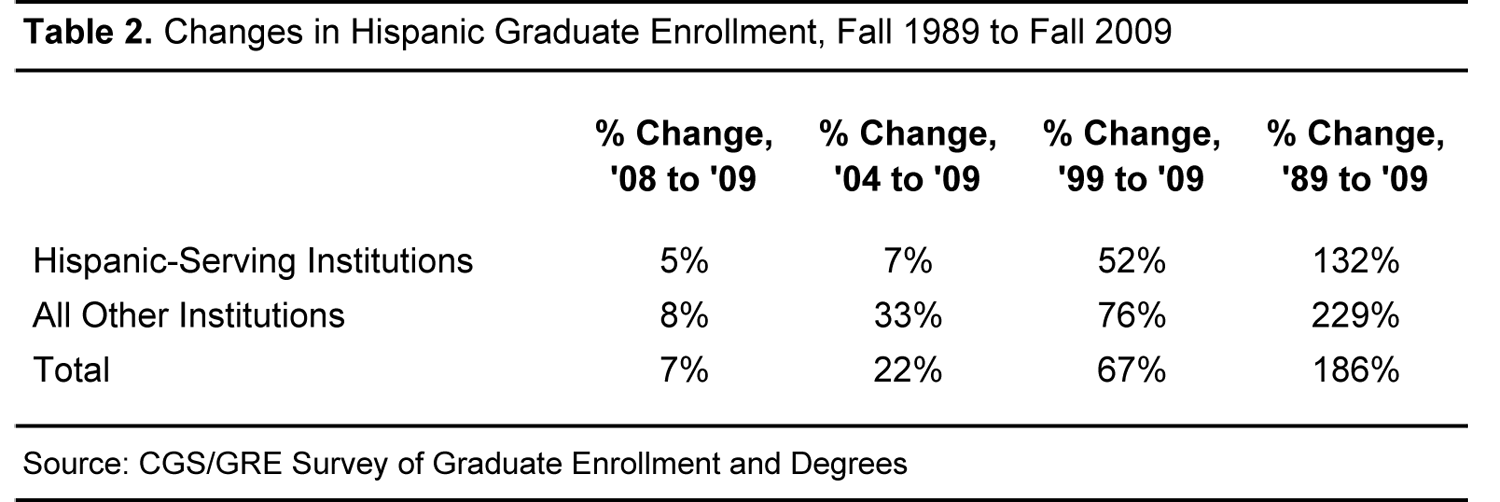

For Hispanic graduate students, the enrollment growth that occurred over the past two decades happened in both HSIs and non-HSIs, but was greater at non-HSIs than at HSIs (see Table 2). Between fall 1989 and fall 2009, Hispanic graduate enrollment increased 229% at non-HSIs compared with 132% at HSIs (Council of Graduate Schools, 2010). Similarly, the rate of increase in Hispanic graduate enrollment between fall 1999 and fall 2009 was 76% at non-HSIs compared with 52% at HSIs. Over the last five years, most of the growth in Hispanic graduate enrollment has been at non-HSIs. Hispanic graduate enrollment increased just 7% at HSIs between fall 2004 and fall 2009, but rose 33% at all other institutions.

Implications

While the gains for Hispanics in graduate education at both HSIs and non-HSIs are encouraging, there remains a long way to go before parity is reached. And the barriers to achieving parity remain great. The two primary barriers are the high dropout rates for Hispanics in high school and the low enrollment rates of Hispanics in undergraduate education. In 2008, 18% of Hispanic 16- through 24-year-olds were not enrolled in high school and had not earned a high school diploma or alternative credential (Chapman, Laird, and KewalRamani, 2010). In contrast, just 4% of Asian/Pacific Islanders, 5% of Whites, and 10% of African Americans were high school dropouts. And among high school graduates ages 16 to 21 in 2006, 79% of Asians and 61% of Whites were enrolled in college, compared with 49% of African Americans and 45% of Hispanics (Davis and Bauman, 2008).

Given these high dropout rates from high school and low enrollment rates in undergraduate education, it is not surprising that the educational attainment of the Hispanic population also lags that of other racial groups. In 2009, just 3% of Hispanics 25 years of age and older in the United States had a graduate degree, compared with 10% of Whites and 6% of African Americans (Snyder and Dillow, 2010). The pathways to graduate school must be improved in order to ensure parity for Hispanics in graduate degree attainment. To achieve this goal will require the participation and support of HSIs as well as non-HSIs.

By Nathan E. Bell, Director, Research and Policy Analysis

References

Chapman, C., Laird, J. and KewalRamani, A. (2010). Trends in High School Dropout and Completion Rates in the United States: 1972–2008. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from http://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch

Council of Graduate Schools. (2010). CGS/GRE Survey of Graduate Enrollment and Degrees. Dataset.

Davis, W. and Bauman, K. (2008). School Enrollment in the United States: 2006. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/2008pubs/p20-559.pdf

Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities. (2011). “Hispanic-Serving Institution Definitions.” Retrieved from http://www.hacu.net/hacu/HSI_Definition_EN.asp?SnID=166172461

Snyder, T. and Dillow, S. (2010). Digest of Education Statistics 2009. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2000). “Resident Population Estimates of the United States by Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin: April 1, 1990 to July 1, 1999, with Short-Term Projection to November 1, 2000.” Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/popest/archives/1990s/nat-srh.txt

U.S. Census Bureau. (2002). “U.S. Summary: 2000.” Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/2002pubs/c2kprof00-us.pdf

U.S. Census Bureau. (2008). “An Older and More Diverse Nation by Midcentury.” Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb08-123.html

U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). “Table 4: Annual Estimates of the Hispanic Resident Population by Sex and Age for the United States: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2009). Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/popest/national/asrh/NC-EST2009/NC-EST2009-04-HISP.xls

(Reprinted from the March 2011 issue of the CGS Communicator)

Through the Current Population Survey (CPS), a monthly sample survey of approximately 60,000 households across the United States, the U.S. Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) collect data on the education level of the U.S. population and the income of employed individuals. The findings from the 2010 CPS surveys confirm that individuals with advanced degrees continue to earn more on average than individuals with lower levels of educational attainment.

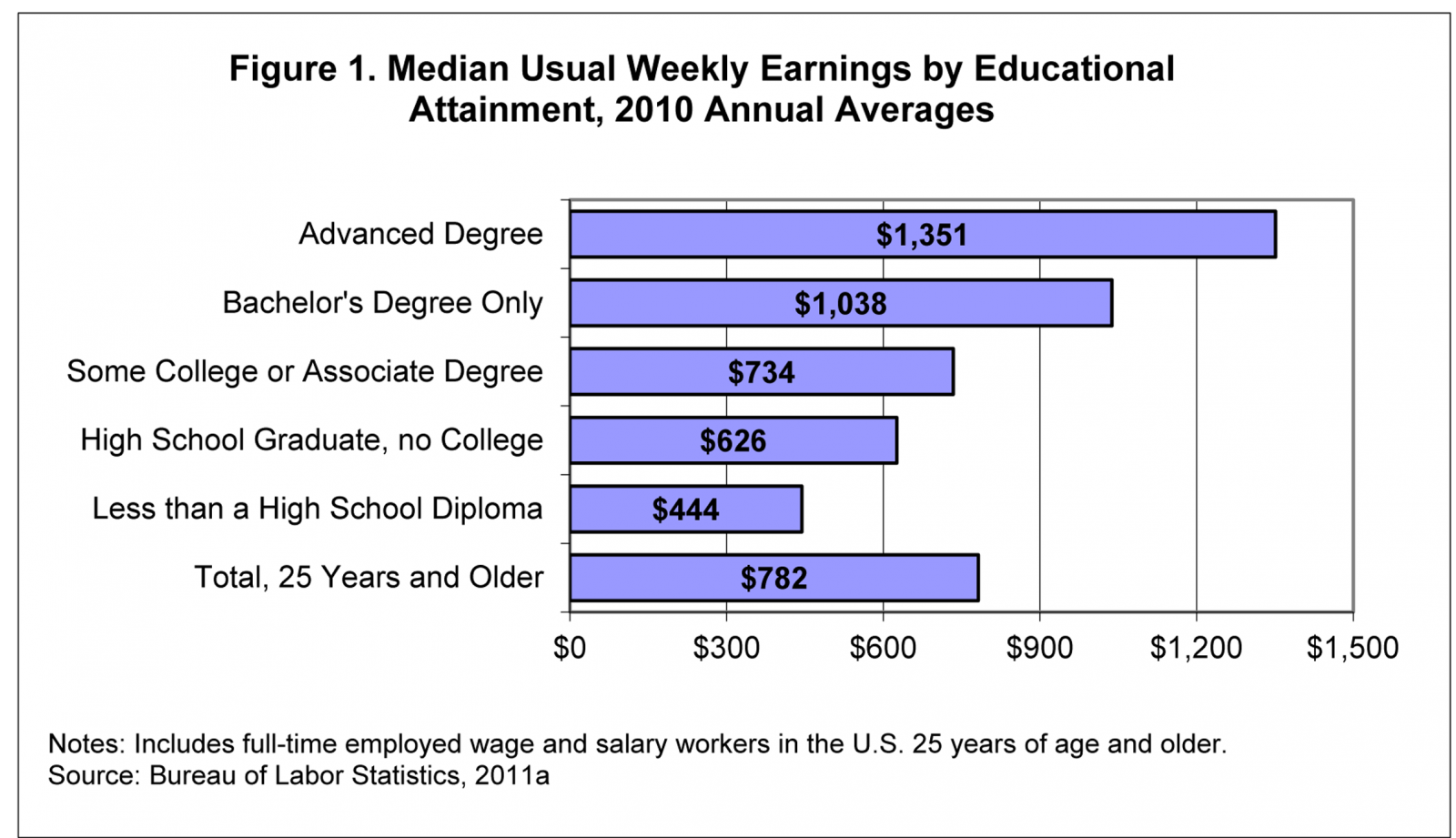

In 2010, among full-time employed wage and salary workers 25 years of age and older, the median usual weekly earnings of individuals with advanced degrees (master’s degrees, doctorates, or first-professional degrees) were $1,351 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011a). This compares with median usual weekly earnings of $1,038 for individuals with a bachelor’s degree as their highest degree and $626 for individuals with only a high school diploma (see Figure 1). This wage premium means that individuals with advanced degrees earned 30% more in 2010 than individuals with a bachelor’s degree as their highest degree and more than twice as much as individuals with only a high school diploma. Overall, the median usual weekly earnings of all wage and salary workers 25 years of age and older was $782.

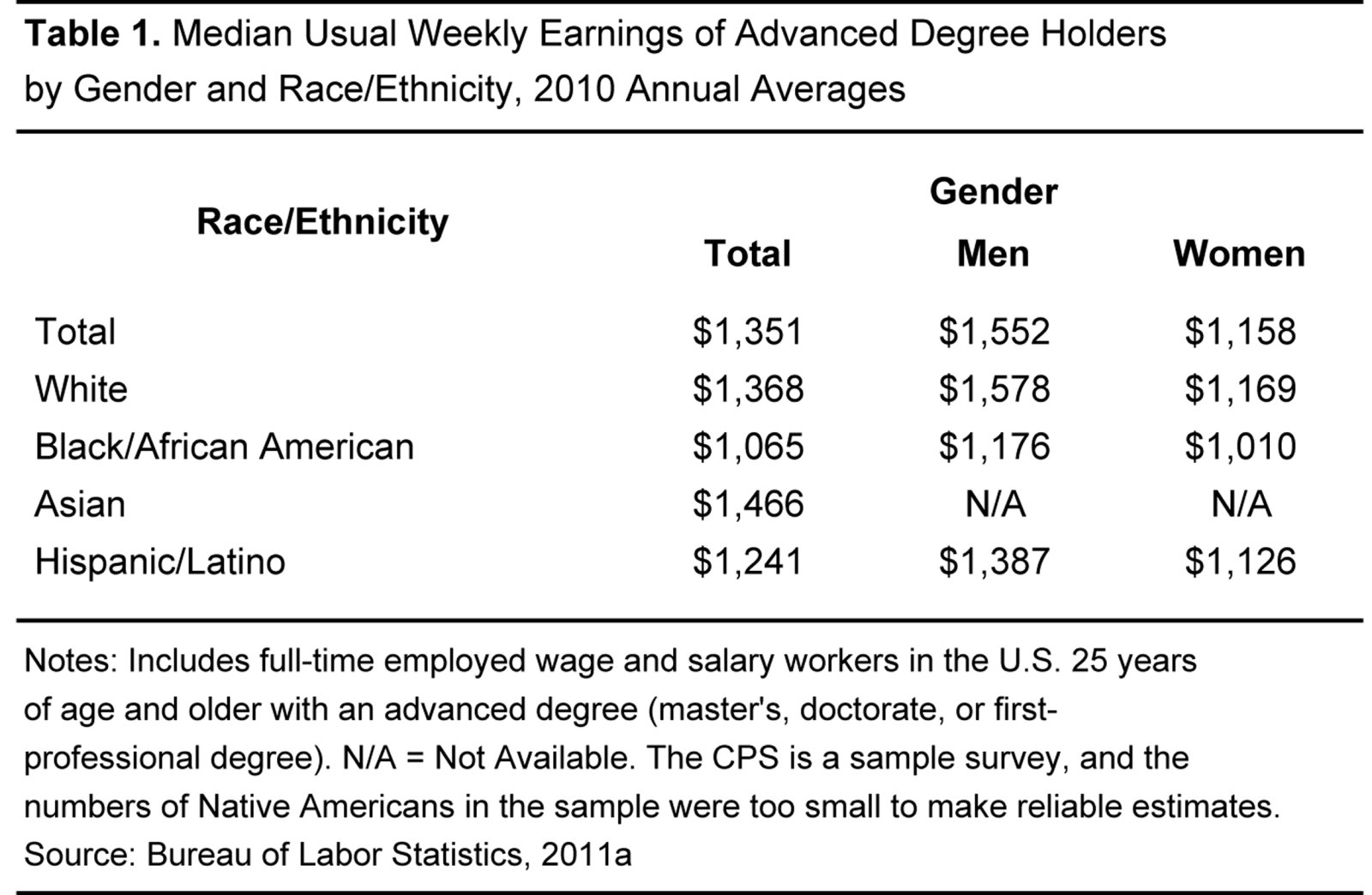

While advanced degree holders earned a median $1,351 per week in 2010, there were large differences by gender and race/ethnicity. Overall, men with advanced degrees earned about 34% more than women with advanced degrees – $1,552 for men versus $1,158 for women (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011a). By race/ethnicity, Asian and white workers with advanced degrees earned more than their Hispanic/Latino and Black/African American counterparts (see Table 1). Median usual weekly earnings ranged from a high of $1,466 for Asian workers to a low of $1,065 for Black/African American workers. Within every race/ethnicity category, men earned more than women (see Table 1). White men earned about 35% more than white women, and Hispanic/Latino men earned about 23% more than Hispanic/Latino women. Black/African American men also earned more than Black/African American women, but the wage premium was smaller than in other race/ethnicity categories, with Black/African American men earning 16% more than Black/African American women. Among all workers with advanced degrees, Black/African American women had the lowest median weekly earnings at $1,010, and white men had the highest median weekly earnings at $1,552, about 54% more than the median weekly earnings of Black/African American women.

Among advanced degree holders, the wage premium for men has remained relatively constant over the past decade. In 2000, the median usual weekly earnings of men were 33% higher than the median usual weekly earnings of women – $1,172 versus $881 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011b). A decade later in 2010, men with advanced degrees earned 34% more than women with advanced degrees as noted above, virtually the same wage premium as in 2000.

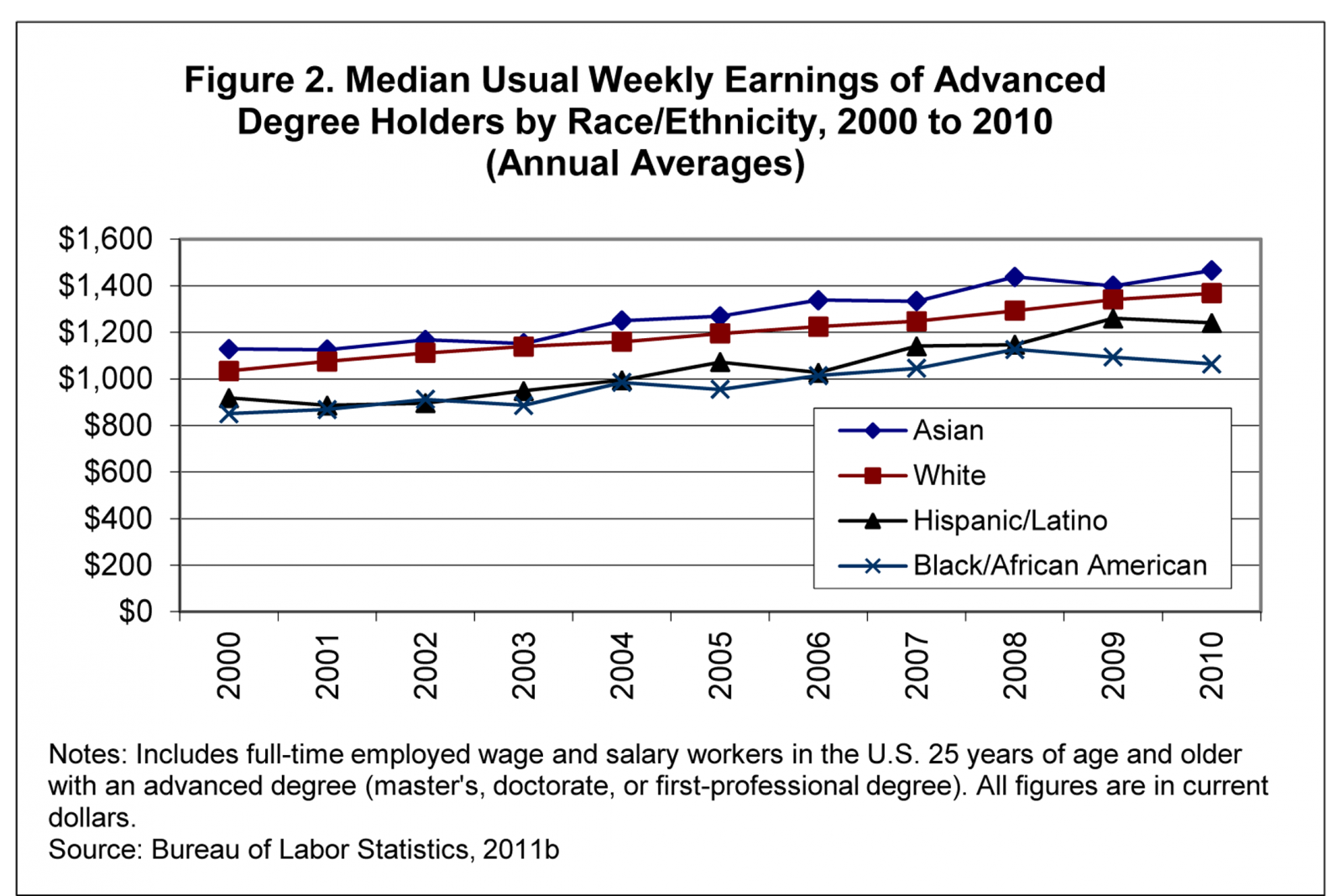

While the wage differences by gender have remained relatively constant over the past decade, wage differences by race/ethnicity have shifted (see Figure 2). In 2000, the median usual weekly earnings of Asians with advanced degrees were 23% higher than the median usual weekly earnings of Hispanics/Latinos ($1,129 versus $919) (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011b). But by 2010, the wage premium for Asians decreased to 18% ($1,466 for Asians versus $1,241 for Hispanics/Latinos), indicating that wages increased faster for Hispanics/Latinos than for Asians over the decade thereby decreasing the gap. Similarly, the median usual weekly earnings for whites with advanced degrees were 13% higher in 2000 than the median usual weekly earnings for Hispanics/Latinos ($1,034 versus $919), and the wage premium for whites decreased to 10% in 2010 ($1,368 for whites versus $1,241 for Hispanics/Latinos).

Not all of the shifts by race/ethnicity were in positive directions; Blacks/African Americans with advanced degrees lost ground on earnings over the past decade compared with their Asian and white peers. In 2000, Asians with advanced degrees earned 33% more than their Black/African American peers ($1,129 versus $851); in 2010, Asians earned 38% more ($1,466 versus $1,065). Whites with advanced degrees earned 22% more than their Black/African American peers in 2000 ($1,034 versus $851); in 2010, they earned 29% more ($1,368 versus $1,065). While median earnings for Blacks/African Americans with advanced degrees increased overall between 2000 and 2010 in current dollars, this gain was outpaced by the gains for Asians and whites. Furthermore, Blacks/African Americans experienced a decline in median earnings in 2009 and 2010 during the recession, thereby adding to the wages differences between Blacks/African Americans and Asians and whites.

The data from the CPS clearly show that higher education is a gateway to careers with higher-earnings potential, but they also reveal that disparities remain in earnings by gender and race/ethnicity. It is important, however, to note that the figures presented in this article do not control for field of study, occupation, length of professional employment, and other variables that might explain some (but not all) of the differences in earnings by gender and race/ethnicity.

Two factors in particular contribute to lower median earnings for women than for men. First, women with advanced degrees are more likely than men to be employed in some occupations in which salaries are lower, such as teaching, and less likely to be employed in some occupations with higher median salaries, such as engineering (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2010). Second, women comprise a larger share of new employees with advanced degrees today than they did even a decade ago. In 1999-00, women earned 58% of all master’s degrees and 44% of all doctorates; by 2008-09 (the latest year for which data are available) they earned 60% of all master’s degrees and 50% of all doctorates (Council of Graduate Schools, 2010). This means that women are more concentrated than men in the portion of the advanced degree workforce that is younger and has fewer years of professional experience. This portion of the workforce tends to have lower earnings than older, more experienced workers.

Similarly, underrepresented minorities (Native Americans, Blacks/African Americans, and Hispanics/Latinos) are also more concentrated in the younger and less experienced portion of the advanced degree workforce. In 1999-00, underrepresented minorities earned 14% of all master’s degrees awarded to U.S. citizens and permanent residents and 11% of all research doctorates, compared with 18% of the master’s degrees and 13% of all research doctorates in 2008-09 (National Science Foundation, 2010 and 2011).

While differences in earnings by gender and race/ethnicity are evident in the CPS data, what is also evident is that regardless of gender or race/ethnicity, individuals with advanced degrees earn a higher median salary than their counterparts with lower levels of educational attainment. Advanced degrees do not guarantee higher wages, but they are often the pathway to occupations with greater economic rewards.

By Nathan E. Bell, Director, Research and Policy Analysis

References

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2010). “Median Weekly Earnings of Full-time Wage and Salary Workers by Detailed Occupation and Sex.” Retrieved from http://bls.gov/cps/cpsaat39.pdf

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2011a). “Table 9. Quartile and Selected Deciles of Usual Weekly Earnings of Full-time Wage and Salary Workers by Selected Characteristics, 2010 Annual Averages.” Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/wkyeng.pdf

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2011b). “Weekly and Hourly Earnings Data from the Current Population Survey.” Retrieved from http://data.bls.gov/onescreen/?survey=le

Council of Graduate Schools. (2010). CGS/GRE Survey of Graduate Enrollment and Degrees. Dataset.

National Science Foundation. (2010). Doctorate Recipients from U.S. Universities: 2009. Retrieved from http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/nsf11306

National Science Foundation. (2011). WebCASPAR Integrated Science and Engineering Resources Data System. Dataset. Accessed February 9, 2011.

(Reprinted from the April 2011 issue of the CGS Communicator)

For more than 25 years, the Council of Graduate Schools, in partnership with the Graduate Record Examinations (GRE) Board, has collected and published data on graduate enrollment and degrees in U.S. colleges and universities (Council of Graduate Schools, 2010). Similar data are published by the Canadian Association for Graduate Studies for institutions in Canada (Canadian Association for Graduate Studies, 2011). While differing definitions and methodologies prevent exact comparisons between the two sources, the data illuminate some similarities as well as some differences in the graduate student populations of the U.S. and Canada.

One major difference between graduate enrollment in the U.S. and in Canada is the size of the graduate student population. Graduate enrollment in the U.S. is more than ten times larger than graduate enrollment in Canada. Institutions responding to the CGS/GRE Survey of Graduate Enrollment and Degrees reported enrolling a total of nearly 1.75 million students in U.S. graduate programs in 2008. In contrast, graduate enrollment in Canada totaled about 172,000 students in that same year.

Graduate enrollment is increasing slightly faster in Canada than in the U.S. Since 1999, graduate enrollment has grown by 5.3% annually on average in Canada, compared with a 3.7% average annual increase in the U.S.

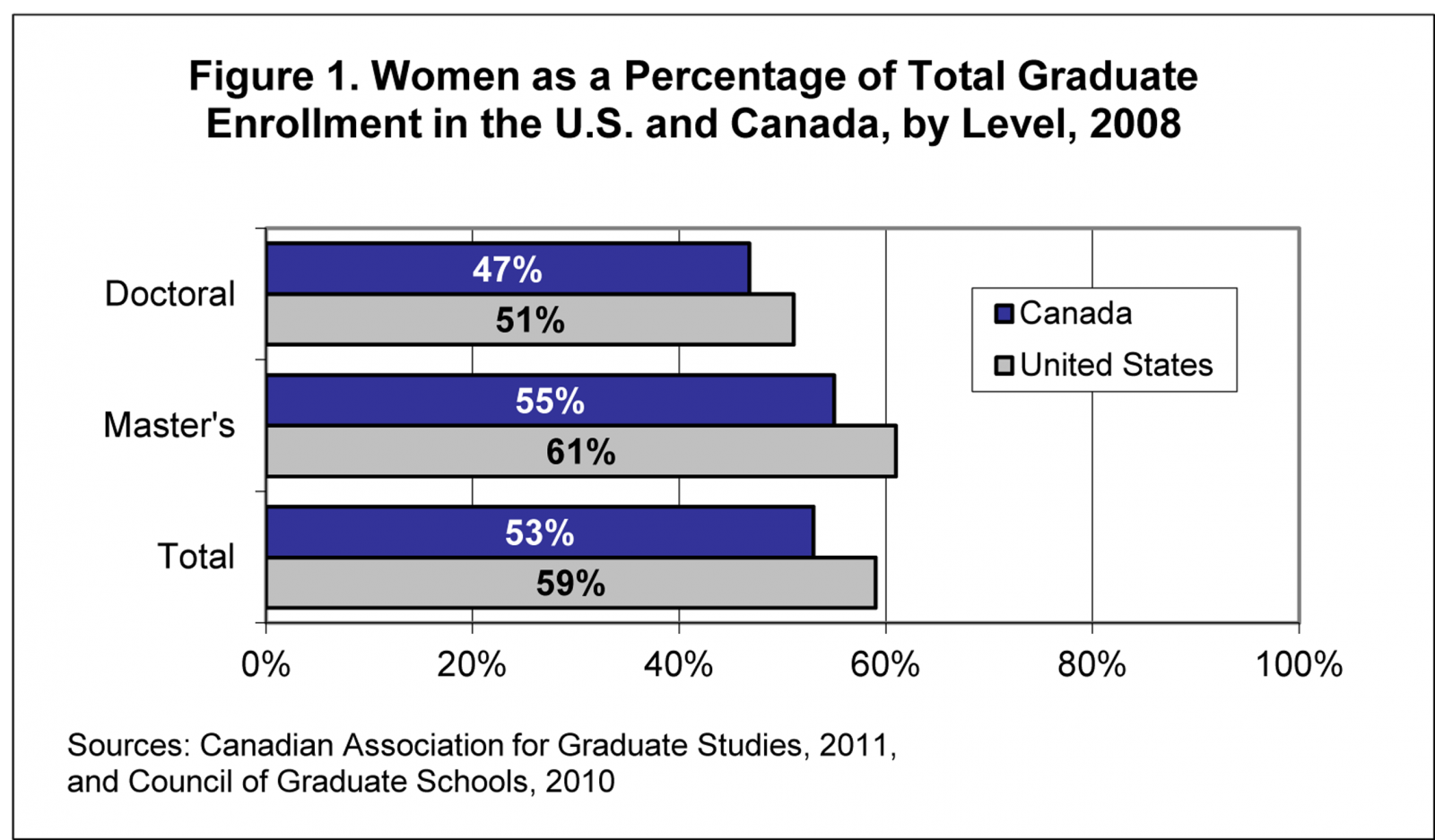

In both the U.S. and Canada, the majority of all graduate students are women. In 2008, women comprised 59% of all U.S. graduate students and 53% of all Canadian graduate students (see Figure 1). In both countries, women accounted for a larger share of master’s enrollment than doctoral enrollment. In the U.S., 61% of all students enrolled in master’s programs in 2008 were women, and 51% of doctoral enrollees were women. Similarly, in Canada women comprised 55% of master’s enrollees and 47% of doctoral enrollees in 2008. The share of women in graduate enrollment is on the rise in both the U.S. and Canada, increasing from 55% in 1999 to 59% in 2008 in the U.S. and from 50% to 53% in Canada over the same time period.

International students comprise a similar share of graduate enrollment in the U.S. and in Canada. In 2008, 16% of all graduate students in U.S. institutions were international, while in Canada, about 15% were international. In both countries, international students are more likely to be enrolled in science and engineering and business fields than in arts and humanities fields. The international student population in both countries increased as a share of total graduate enrollment between 1999 and 2008, but growth in Canada outpaced growth in the U.S. The international share of graduate enrollment increased from about 15.5% to 16% in the U.S. between 1999 and 2008, compared with a gain from 12% to 15% in Canada over the same time period.

International students at Canadian institutions are most likely to be from countries in Eastern and Southern Asia. At the master’s level in Canada, 3.1% of all students come from Eastern Asia and 2.0% from Southern Asia. At the doctoral level, 3.8% come from Southern Asia and 3.4% from Eastern Asia. While the CGS/GRE Survey of Graduate Enrollment and Degrees does not collect data on country of origin for international students attending institutions in the U.S., data from the CGS International Graduate Admissions Survey show that about half of all international students at U.S. graduate schools are from China, India, and South Korea (Bell, 2010), indicating the importance of students from Asian countries to the graduate school populations of both countries.

Graduate students in the U.S. are more likely to be enrolled part-time than graduate students in Canada. In 2008, 45% of all U.S. graduate students were enrolled part-time, compared with 26% of Canadian graduate students. In both countries, graduate students in education were among the most likely to be enrolled part-time.

In both the U.S. and Canada, the majority of all graduate degrees awarded each year are master’s degrees. In Canada, about 36,500 master’s degrees were awarded in 2008, compared with 5,400 doctorates. In the U.S., institutions responding to the CGS/GRE Survey of Graduate Enrollment and Degrees reported awarding over 488,000 master’s degrees in 2008, compared with about 56,000 doctorates.

In the U.S., education and business were the largest broad fields at the master’s level in 2008, accounting for 29% and 23%, respectively, of the master’s degrees awarded that year. In Canada, the largest broad field was business, management and public administration, accounting for 29% of all master’s degrees in 2008. The field of education is much smaller in Canadian institutions, with just 11% of all master’s degrees in 2008 awarded in that broad field.

At the doctoral level in the U.S., engineering and physical sciences were the largest broad fields, each accounting for about 15% of all doctorates awarded that year. In Canada, the broad field of physical and life sciences accounted for the largest share of doctorates awarded in 2008 (26%), followed by architecture, engineering, and related technologies (19%). While there are differences in the taxonomies used in the two data sources, the broad fields of engineering and physical sciences account for a large portion of the doctorates awarded each year in both Canada and the U.S.

While the size of graduate education in the U.S. dwarfs that of Canada, both countries have similar percentages of international students and similar trends in the participation of women in graduate education. They also share some similarities in the fields of study that comprise the majority of the graduate degrees awarded and the countries of origin of their international graduate students. And Canada and the U.S. have both experienced an increase in graduate enrollment over the past decade. The two data sets examined in this article, while not directly comparable, clearly document some shared trends in graduate education and highlight the value placed on graduate education in both Canada and the U.S.

By Nathan E. Bell, Director, Research and Policy Analysis

References

Bell, N.E. (2010). Findings from the 2010 CGS International Graduate Admissions Survey, Phase III: Final Offers of Admission and Enrollment. Washington, DC: Council of Graduate Schools.

Canadian Association for Graduate Studies. (2011). 39th Statistical Report: 1999-2008. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Association for Graduate Studies.

Council of Graduate Schools. (2010). CGS/GRE Survey of Graduate Enrollment and Degrees. Dataset.

(Reprinted from the May 2011 issue of the CGS Communicator)

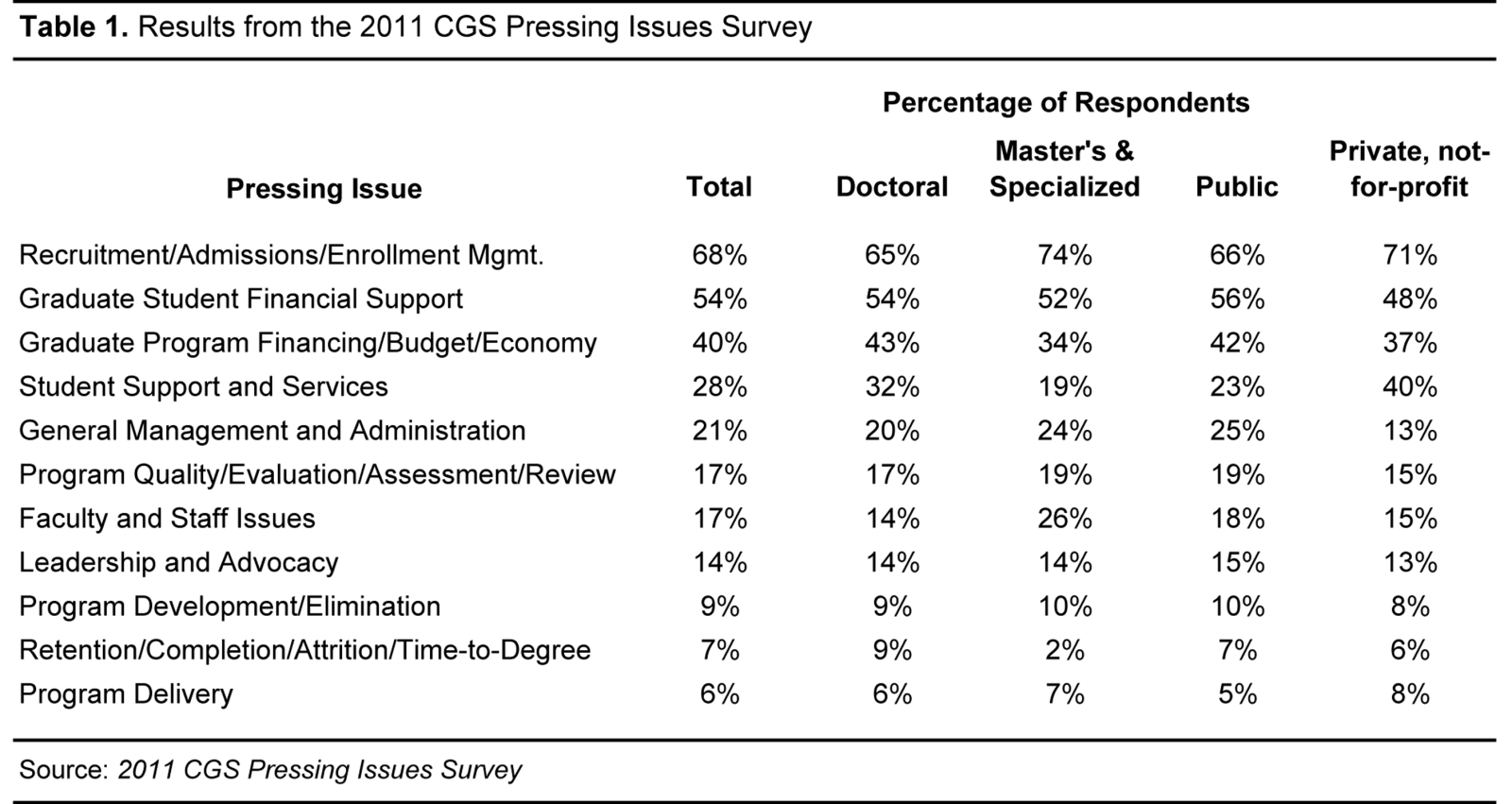

Graduate deans report that their top pressing issues in 2011 are about recruitment, admissions, and enrollment management, according to the Council of Graduate Schools’ (CGS) annual Pressing Issues Survey. Each year, CGS asks graduate deans at member institutions to identify the three most important or “pressing” issues or challenges they currently face. The findings from this Pressing Issues Survey inform CGS about the concerns of graduate deans and help to shape sessions at Summer Workshops, Annual Meetings, and other forums, as well as future best practices projects. The survey has been conducted annually as part of the CGS International Graduate Admissions Survey, Phase I: Applications since 2004 and through the CGS membership survey and other surveys in prior years.

The 2011 Phase I survey was sent to 494 U.S. colleges and universities that were members of CGS as of January 2011. A total of 230 institutions responded to the survey, for a response rate of 47% (Bell, 2011). About 93% (213) of the Phase I survey respondents wrote in one or more pressing issues in response to this open-ended question, and the analyses below are limited to these 213 respondents. They included 155 doctoral institutions, 48 master’s-focused institutions, and 10 institutions classified as baccalaureate or specialized in the 2010 basic Carnegie Classifications. Sixty-two private, not-for-profit institutions responded to the Pressing Issues Survey, along with 151 public institutions. By geographic region, 54 of the responding institutions were in the Midwest, 42 were in the Northeast, 36 in the West, and 81 in the South. Responses to the Pressing Issues Survey were coded into broad categories. Since respondents were able to write in up to three pressing issues, the percentages sum to more than 100%.

Pressing Issues in 2011

The top pressing issue identified by graduate deans was recruitment, admissions, and enrollment management, mentioned by more than two-thirds (68%) of all respondents (see Table 1). Within this category, respondents mentioned competition for prospective graduate students, challenges in attracting a diverse applicant pool, recruiting international students, and recruiting quality graduate students, among other concerns. Respondents from master’s & specialized institutions were more likely to mention recruitment, admissions, and enrollment management than graduate deans from doctoral institutions (74% vs. 65%), and respondents from private, not-for-profit institutions were more likely to indicate that this was a pressing issue than those at public institutions (71% vs. 66%).

Graduate student financial support was the second most commonly mentioned pressing issue, with 54% of all respondents saying this was a concern. This category includes health insurance for graduate students, as well as direct support through assistantships, fellowships, etc. Graduate deans from doctoral institutions and master’s & specialized institutions were nearly equally as likely to indicate that graduate student financial support was a concern (54% vs. 52%). Respondents from public institutions, however, were more likely to note graduate student financial support as a pressing issue than respondents at private, not-for-profit institutions (56% vs. 48%).

Graduate program financing, dealing with budget cuts, and issues related to the economy ranked third (40%). Respondents from doctoral institutions were more likely to mention this issue than respondents from master’s & specialized institutions (43% vs. 34%), and respondents from public institutions were more likely to indicate that this issue was a concern than those from private, not-for-profit institutions (42% vs. 37%).

Student support and services was ranked as the fourth most pressing issue this year (28%). Within this category, respondents mentioned advising and mentoring, professional development for graduate students, career advice, and job placement assistance, among other concerns. Respondents from doctoral institutions were more likely to mention student support and services than graduate deans from master’s & specialized institutions (32% vs. 19%), and respondents from private, not-for-profit institutions were more likely to indicate that this was a pressing issue than those at public institutions (40% vs. 23%).

The percentages of respondents who mentioned the remaining pressing issues are shown in Table 1. General management and administration (21%) includes a wide variety of issues focused on areas such as policies and procedures, data management, and communications. All issues related to program quality; the evaluation, assessment, or review of graduate programs; accreditation; and student learning outcomes were grouped together as program quality, evaluation, assessment, and review (17%). The category of faculty and staff issues (17%) mainly includes responses about the challenges of dealing with faculty and staff shortages, primarily due to budget cuts. The category of leadership and advocacy (14%) includes responses related to promoting graduate education and communicating the value of graduate education to internal and external stakeholders, among other related issues. All responses related to developing or eliminating programs were grouped as program development/elimination (9%), but the vast majority of responses in this category concerned program development rather than program elimination. Issues surrounding retention, completion, attrition, and time-to-degree (7%) are also grouped together. Finally, all responses related to program delivery, including the delivery of online, distance, interdisciplinary, and joint and dual programs are grouped as program delivery (6%).

Pressing Issues by Carnegie Classification and Institutional Control

The rank order of the top three pressing issues was the same for respondents from doctoral institutions as it was for respondents from master’s & specialized institutions (see Table 1). In both cases recruitment, admissions, and enrollment management was the top issue (65% and 74%, respectively), graduate student financial support was ranked second (54% and 52%, respectively), and graduate program financing, dealing with budget cuts, and issues related to the economy ranked third (43% and 34%, respectively). Respondents from doctoral institutions were more likely than respondents from master’s & specialized institutions to mention student support and services (32% vs. 19%), but they were less likely to mention faculty and staff issues (14% vs. 26%).

The findings for respondents from public institutions mirror the overall findings, with recruitment, admissions, and enrollment management; graduate student financial support; and graduate program financing, dealing with budget cuts, and issues related to the economy as the first, second, and third most pressing issues, respectively (see Table 1). At private, not-for-profit institutions, recruitment, admissions, and enrollment management and graduate student financial support were also the first and second most pressing issues, but the third most pressing issue was student support and services.

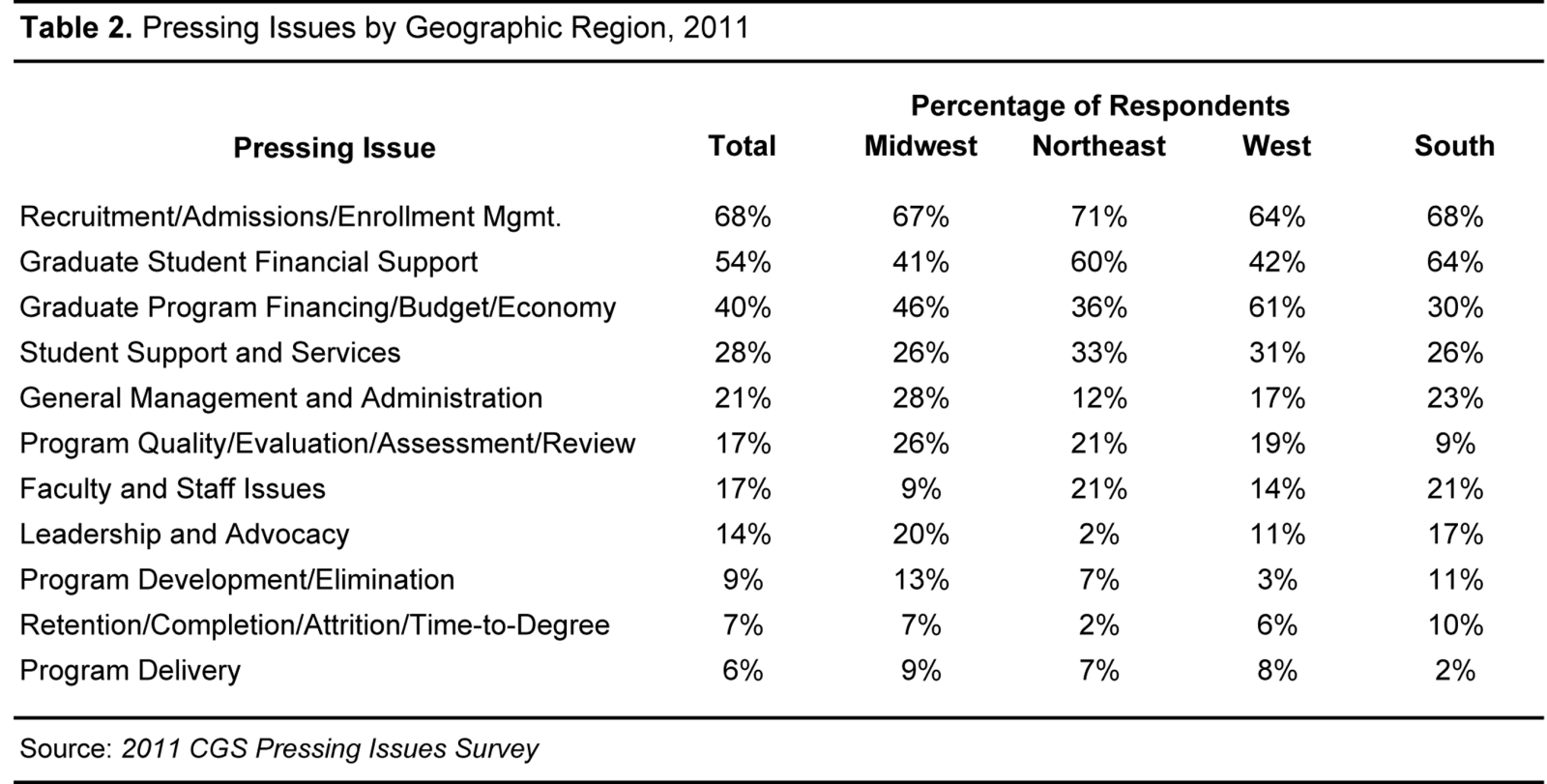

Pressing Issues by Geographic Region

Recruitment, admissions, and enrollment management was the top pressing issue identified by graduate deans at institutions located in all four regions of the United States (see Table 2). The percentage of respondents indicating this area as a pressing issue ranged from a low of 64% of respondents in the West to a high of 71% of respondents in the Northeast. The second and third most pressing issues varied by the geographic region of the responding institutions. Among respondents in the Northeast and South, graduate student financial support was the second most pressing issue and graduate program financing/budget/economy was the third most pressing issue. In contrast, among respondents in the Midwest and West, graduate program financing/budget/economy was the second most pressing issue and graduate student financial support was the third most pressing issue. Respondents from institutions in the Northeast and South were more likely to mention faculty and staff issues than respondents from the Midwest and West. Respondents from the Midwest and South were more likely to indicate that leadership and advocacy was a pressing issue than respondents from the Northeast and West.

Historical Comparison of Pressing Issues

Articles in previous years about the Pressing Issues Survey have provided an examination of the changes in pressing issues over time. Over the past several years, however, there have been variations in coding among researchers, as well as variations in the broad categories used to group issues, meaning that such an examination of changes over time is inexact. Rather than presenting rankings of pressing issues categories over time, it is better to simply touch on the issues that remain among the top concerns of graduate deans each year.

Two broad topics in particular have been mentioned frequently by graduate deans over the past five years: graduate student financial support and recruitment, admissions, and enrollment management. In most recent years, these have been among the two most pressing issues faced by graduate deans. Issues related to graduate program financing, dealing with budget cuts, and the economy have also been mentioned frequently by graduate deans, particularly in the last three years. General management and administration issues have also been cited as concerns in recent years, but given the wide variety of issues that are typically grouped within this category, the specific challenges have varied from year to year.

Conclusion

The results of this year’s Pressing Issues Survey reveal that the majority of graduate deans view recruitment, admissions, and enrollment management as their top concern, as they face issues related to competition for prospective graduate students, challenges in attracting a diverse applicant pool, recruiting international students, and recruiting quality graduate students, among other concerns. They also remain concerned about graduate student financial support and about graduate program financing, dealing with budget cuts, and issues related to the economy. The latter is often reflected in other broad categories as well, with respondents mentioning concerns about the effect of budget cuts and the economy on other aspects of graduate education, including recruiting budgets, personnel, and program delivery. Overall, the results of the Pressing Issues Survey reveal the continued focus of graduate deans on recruiting, enrolling, and supporting high quality graduate students; on offering high quality graduate programs that produce graduates ready to meet the demands of the 21st century global economy; and on communicating the role and value of graduate education.

By Nathan E. Bell, Director, Research and Policy Analysis

References:

Bell, N.E. 2011. Findings from the 2011 CGS International Graduate Admissions Survey, Phase I: Applications. Washington, DC: Council of Graduate Schools.

(Reprinted from the June 2011 issue of the CGS Communicator)

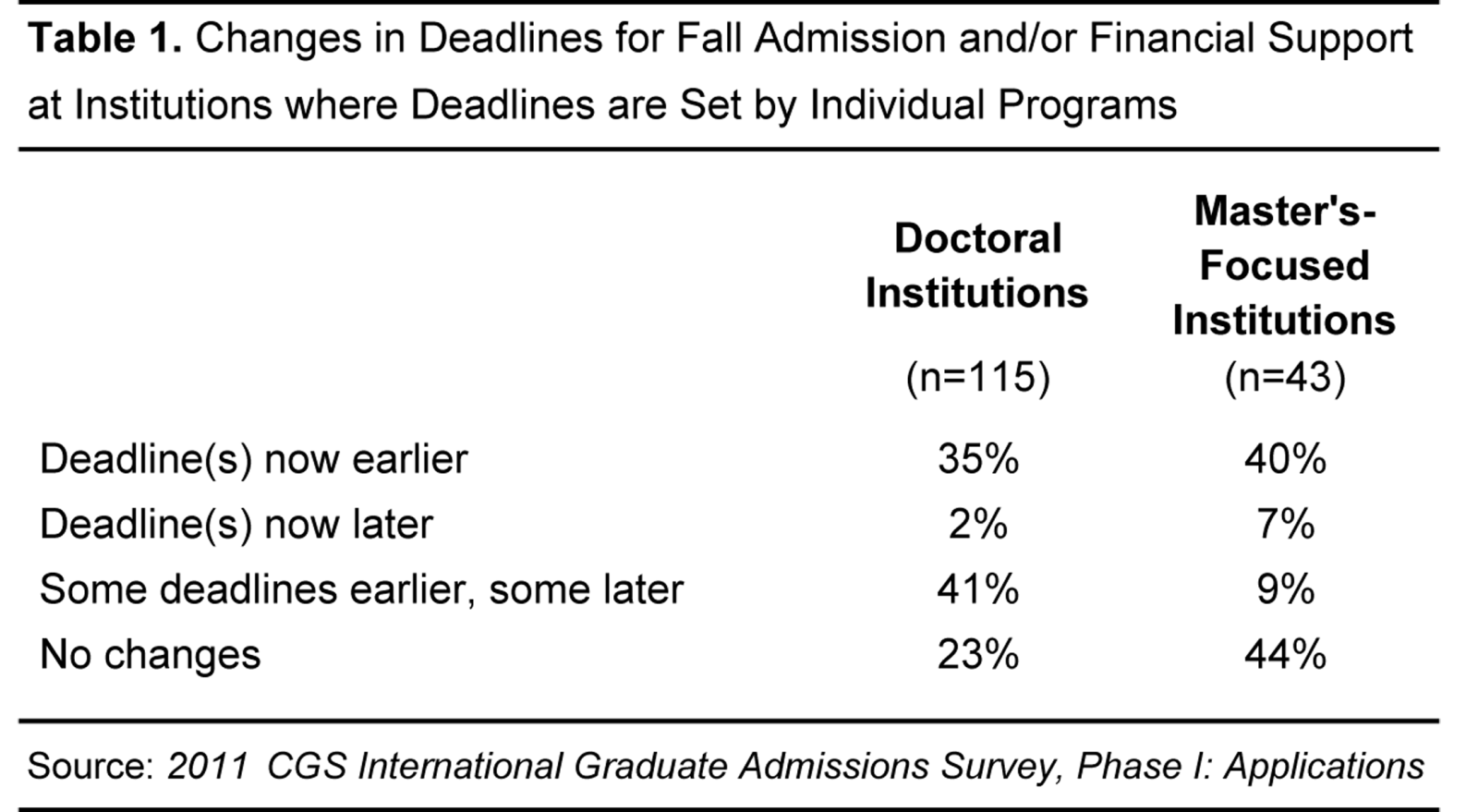

The 2011 CGS International Graduate Admissions Survey, Phase I: Applications included a series of special questions about application and financial support deadlines for graduate students. The questions were designed to gather information about how deadlines were set and whether there have been any changes to deadlines in recent years. This article presents a brief analysis of the responses to those questions.

Survey Methodology and Response Rate

In January 2011, a link to the 2011 Phase I survey was e-mailed to the graduate dean (or equivalent) at all 494 U.S. colleges and universities that were members of CGS. A total of 232 institutions responded to one or more of the special questions on application deadlines, for a response rate of about 47%. The analyses presented below are limited to these 232 respondents. They included 164 doctoral institutions, 57 master’s-focused institutions, and 11 institutions classified as baccalaureate or specialized in the 2010 basic Carnegie Classifications. Sixty-seven private, not-for-profit institutions responded to one or more of the application deadline questions, along with 165 public institutions. By geographic region, 60 of the responding institutions are in the Midwest, 46 are in the Northeast, 38 are in the West, and 88 are in the South.

Application Deadlines

Institutions were first asked, “Which one of the following best describes your institution’s application deadline(s) for fall admission at the graduate level?” Choosing from among three possible response options, the majority (53%) of the respondents indicated that application deadlines are set by individual programs. Nearly one-third (31%) said that the deadlines are set by individual programs, with a final deadline set by the institution or graduate school. The remaining 17% reported that there is an institution-wide deadline set by the institution or graduate school.

There were no statistically significant differences in responses by Carnegie classification or geographic region, but private, not-for-profit institutions were more likely than public institutions to report that application deadlines are set by individual programs (58% vs. 50%) and that there is an institution-wide deadline set by the institution or graduate school (24% vs. 14%). Private, not-for-profit institutions were less likely than their public counterparts to report that that deadlines are set by individual programs, with a final deadline set by the institution or graduate school (18% vs. 36%).

Changes to Application and Financial Support Deadlines

The next two questions related to changes in application deadlines for fall admission and/or financial support for graduate students, asking whether any deadlines have changed within the last three years. Since these two questions also addressed financial support—unlike the previous question which just focused on application deadlines—the findings are somewhat different. The first of these two questions collected data for respondents from institutions where deadlines for fall admission and/or financial support are set by the institution or graduate school, and read as follows: “If deadlines for fall admission and/or financial support are set by the institution or graduate school, have any of those deadlines changed within the last three years?” The second question collected data for respondents from institutions where deadlines for fall admission and/or financial support are set by individual programs, and read as follows: “If deadlines for fall admission and/or financial support are set by individual programs, are you aware of programs within your institution that have changed any deadlines for admission and/or financial support within the last three years?” Ninety-three institutions responded to both of these two questions, presumably because some application and/or financial support deadlines are set by the institution or graduate school and other application and/or financial support deadlines are set by individual programs.

Among the 143 institutions responding to the first of these two questions, thereby indicating that at least some deadlines for fall admission and/or financial support are set by the institution or graduate school, 62% reported that those deadlines have not changed within the last three years. Three out of ten respondents (30%) reported that the deadlines are now earlier, while 8% said that the deadlines are now later. (Eighty-six respondents selecting ‘not applicable’ and three institutions not responding to this question were excluded from these calculations.) There were no statistically significant differences in responses to this question by Carnegie classification, geographic region, or institutional control.

The respondents to this question were then asked to indicate which types of deadlines changed within the last three years. Among the 43 respondents indicating that deadlines are now earlier, 67% reported that the deadline for international admissions changed, 51% said that the deadline for domestic admissions changed, and 49% said that the deadline for students seeking financial support changed. Among the 11 respondents indicating that deadlines are now later, eight respondents reported that the deadline for international admissions changed, five respondents said that the deadline for domestic admissions changed, and only one said that the deadline for students seeking financial support changed.

Among the 164 institutions responding to the second of these two questions, thereby indicating that at least some deadlines for fall admission and/or financial support are set by individual programs, 37% reported that the deadlines are now earlier, 31% said that some deadlines are now earlier and some are now later, 29% said that the deadlines have not changed within the last three years, and 3% said that the deadlines are now later. (Sixty respondents selecting ‘not applicable/not aware of any changes’ and eight institutions not responding to this question were excluded from these calculations.) Doctoral institutions were more likely than master’s-focused institutions to indicate that deadlines have changed, with more than four out of ten indicating that some deadlines are now earlier and some are now later, as shown in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences in responses to this question by geographic region or institutional control.

As with the previous question, respondents were then asked to indicate which types of deadlines changed within the last three years. Among the 60 respondents indicating that deadlines are now earlier, 70% reported that the deadline(s) for international admissions changed, 75% said that the deadline(s) for domestic admissions changed, and 40% said that the deadline(s) for students seeking financial support changed. Among the five respondents indicating that deadlines are now later, three respondents reported that the deadline(s) for international admissions changed, four respondents said that the deadline(s) for domestic admissions changed, and only one said that the deadline(s) for students seeking financial support changed. A total of 51 respondents indicated that some deadlines are now earlier and some are now later, and among these respondents the vast majority reported that the deadlines for international admissions (84%) and domestic admissions (88%) changed. More than half (53%) indicated that the deadline(s) for students seeking financial support changed.

Conclusions

Responding institutions were more likely to indicate that application deadlines for fall admission are set by individual programs, rather than by the institution or graduate school. Institutions where deadlines for fall admission and/or financial support are set by individual programs were nearly twice as likely to report that deadlines have changed within the last three years as institutions where deadlines are set by the institution or graduate school—seven out of ten of the former reported changes to deadlines compared with four out of ten of the latter. The majority of institutions changing deadlines made those deadlines earlier, rather than later. For example, among institutions where deadlines are set by the institution or graduate school, respondents indicating earlier deadlines outnumbered respondents indicating later deadlines by a factor of four to one.

The data presented here are admittedly from a relatively small sample of the institutions that award graduate degrees in the United States. And since the data were collected through a survey that primarily gathers data on international students, the responses may not be representative of all institutions, particularly those with smaller numbers of international students. That being said, the data suggest that there may be a trend toward earlier deadlines for applications and financial support at U.S. graduate schools, and furthermore, that this change affects both international and domestic students. More information is needed, however, to interpret the true meaning of this finding. For example, the survey did not collect data on the actual deadline dates, so it is unclear how much deadlines have shifted (e.g., by one week, two weeks, etc.). The reasons for changes to deadlines are also not fully known. Changes to deadlines may have been made to align an institution with the deadlines of other institutions, to differentiate an institution from others, to align various deadlines within an institution, or for any other number of reasons. While the survey data do not illuminate the reasons for changes to deadlines, they clearly show that some institutions and graduate programs are making changes to deadlines for fall admission and financial support.

By Nathan E. Bell, Director, Research and Policy Analysis

(Reprinted from the July 2011 issue of the CGS Communicator)

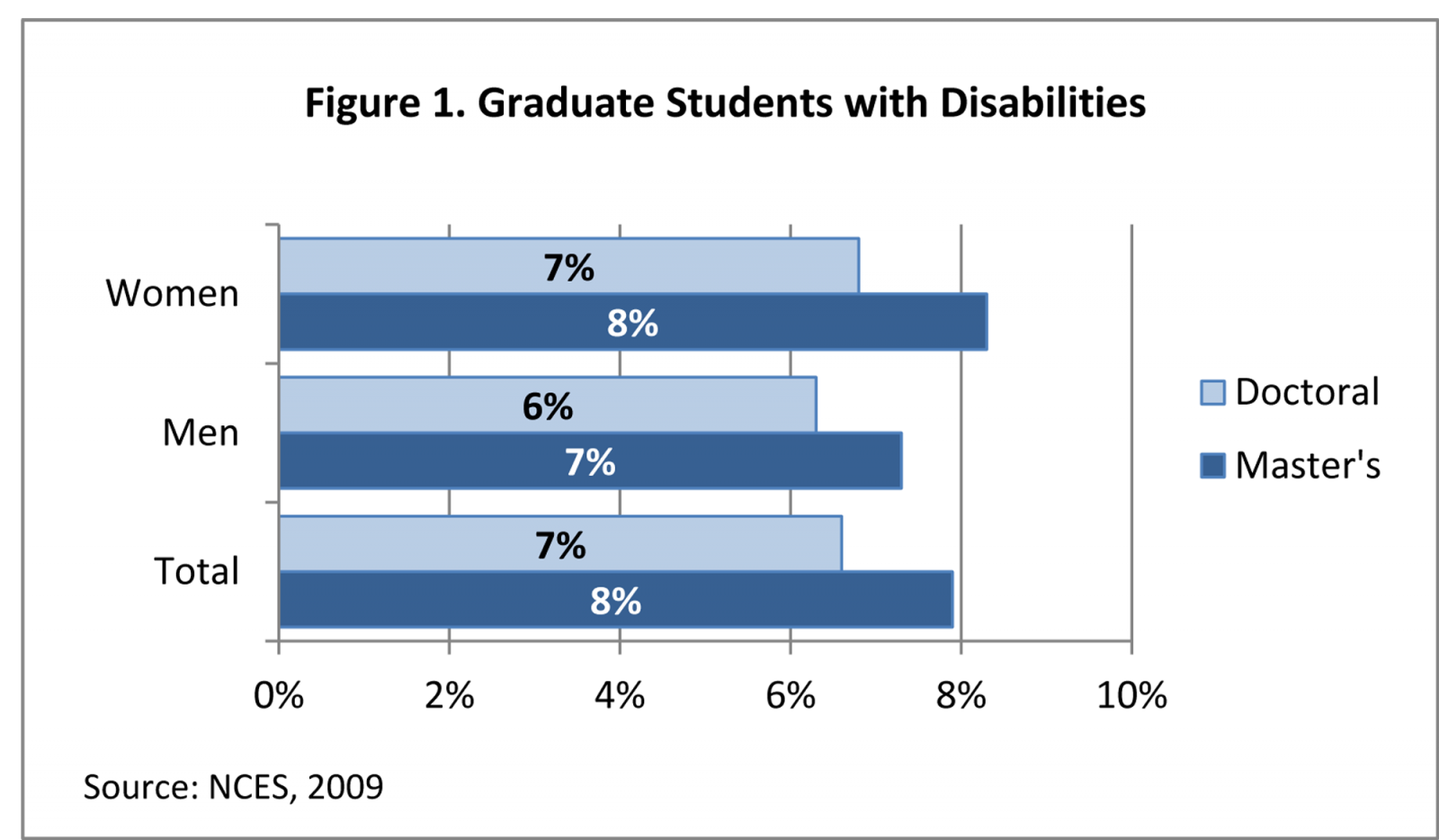

According to data from the American Community Survey, about 6% of the U.S. population ages 5 to 20 and 13% of the U.S. population ages 21 to 64 had a disability in 2007 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011a and 2011b). Data on the participation of individuals with disabilities in graduate education is not as widely disseminated as data on graduate enrollment by other student characteristics, such as gender, citizenship, and race/ethnicity, but some data do exist to shed light on this topic.

One somewhat unlikely source of information on graduate students with disabilities is the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS). The main purpose of the NPSAS is to examine how students finance their education, but the survey data can also provide estimates of graduate enrollment by student characteristics, including disability status. The NPSAS defines a disability as a condition such as blindness; deafness; severe vision or hearing impairment; substantial limitation of one or more basic physical activities such walking, climbing stairs, reaching, lifting, or carrying; or any other physical, mental, emotional, or learning condition that lasts six months or more.

According to data from the most recent NPSAS, about 8% of master’s students and 7% of doctoral students in academic year 2007-08 had some type of disability (NCES, 2009). At both the master’s and doctoral levels in 2007-08, women were slightly more likely than men to report having a disability—8% vs. 7% at the master’s level and 7% vs. 6% at the doctoral level, as shown in Figure 1.

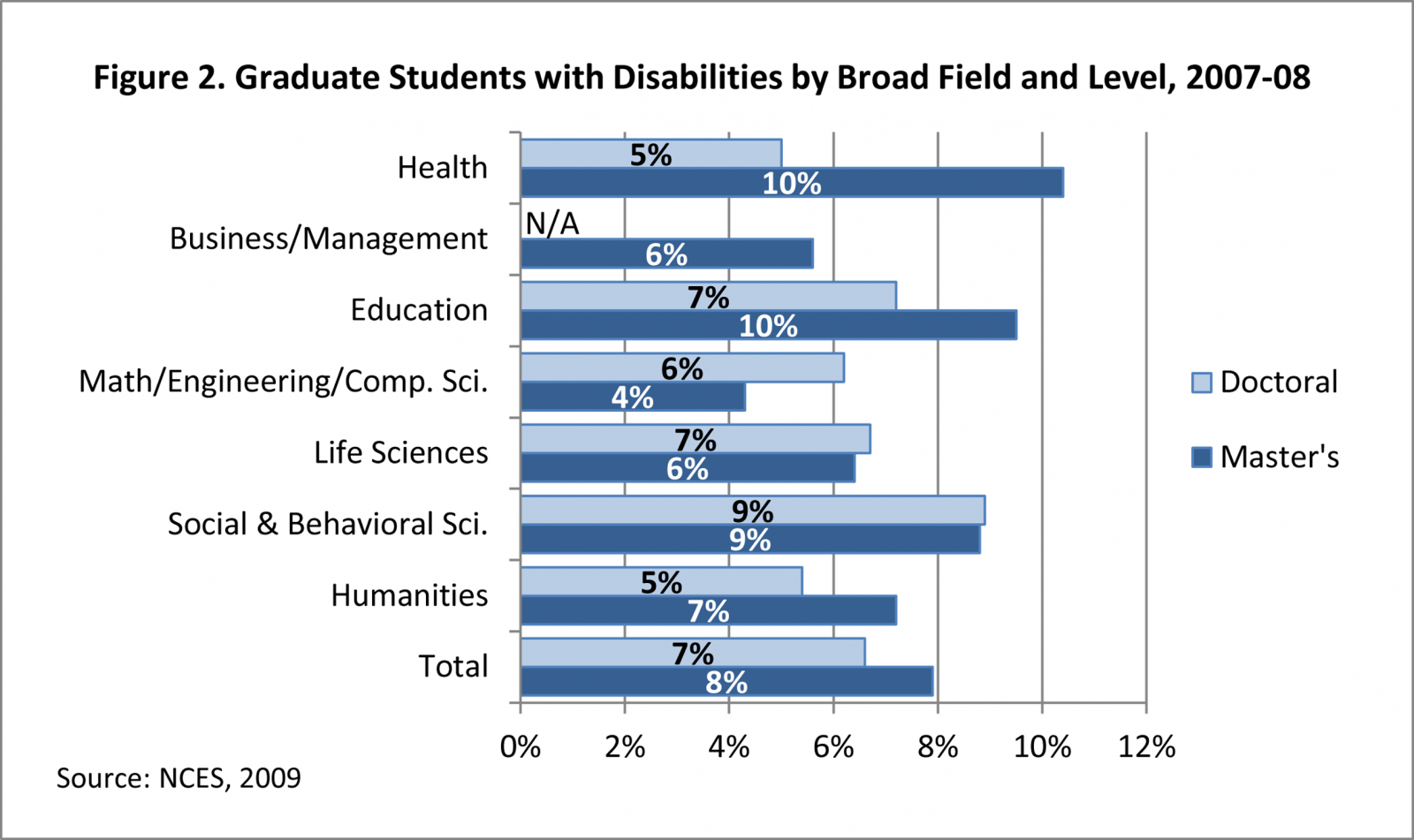

The NPSAS data also show that the percentage of graduate students who reported having some type of disability in academic year 2007-08 varied by broad field. At the master’s level, students enrolled in mathematics, engineering, and computer science were least likely to report having a disability (4%), while master’s students in the broad fields of health and education were most likely to report having a disability (both 10%), as shown in Figure 2. At the doctoral level, 5% of students in the broad fields of health and humanities reported having some type of disability, compared with 9% of doctoral students in social and behavioral sciences. Data for business/management at the doctoral level were suppressed due to the small sample size.

In addition to showing the percentage of students with a disability by broad field, the NPSAS data also illustrate the distribution of students with and without disabilities across broad fields. In most cases, the distributions were very similar in 2007-08, with students with and without disabilities being distributed in similar shares across most broad fields of study. For example, at the master’s level, 8% of all students with disabilities and 7% of all students without disabilities were enrolled in social and behavioral sciences. Similarly, 14% of all doctoral students with disabilities, as well as 14% of all doctoral students without disabilities, were enrolled in life sciences. But, there were some cases in which the distributions varied. At the master’s level, students with disabilities were more likely to be in education than their counterparts without disabilities; 35% of all master’s students with disabilities were enrolled in education in 2007-08 compared with 29% of all master’s students without disabilities. In contrast, master’s students with disabilities were less likely to be in business/management than students without disabilities (18% vs. 25%). At the doctoral level, students with disabilities were more likely to be enrolled in social and behavioral sciences then students without disabilities (19% vs. 13%).

A second source of data on graduate students with disabilities is the annual Survey of Earned Doctorates (SED), which is administered to recipients of research doctorates in the United States. In its definition of disability, the SED includes blindness/visual impairment, physical/orthopedic disability, deafness/hard of hearing, learning/cognitive disability, vocal/speech disability, and other/unspecified disabilities. According to the SED, 1.5% of all doctorate recipients in 2009 reported having one or more disabilities of any type (National Science Foundation, 2010). This percentage is considerably lower than the NPSAS estimate of the percentage of doctoral enrollees with disabilities, but it is important to note that the populations and methodologies of the two surveys are very different, which might explain the difference between the two figures. First, the SED only collects data on recipients of research doctorates, while the NPSAS includes in its estimate students enrolled in all doctoral programs, including practice-oriented programs such as the Psy.D., DPT and Ed.D. In addition, the response rate for the SED is typically in the 90-95% range each year, while the NPSAS is a sample survey based on a much smaller subset of doctoral students and therefore is subject to sampling errors. Finally, the SED reports data on doctorate recipients while the NPSAS surveys doctoral enrollees. While it is possible that there are differences in completion rates between students with and without disabilities which could result in students with disabilities comprising a higher share of enrollees than degree recipients, the available datasets are unable to indicate whether this is the case.

The SED provides disaggregated data by field of study and student demographics. By broad field of study, the percentage of doctorate recipients with one or more disabilities of any type ranged from a low of 0.7% in engineering to a high of 2.6% in education. By gender, 1.3% of male doctorate recipients and 1.6% of female doctorate recipients reported a disability. And by citizenship, U.S. citizen and permanent resident doctorate recipients were more likely than temporary visa holders to report having a disability – 2.1% vs. 0.4%.

The National Science Foundation also publishes the most accessible, albeit somewhat narrowly focused, source of data on individuals with disabilities, Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering (National Science Foundation, 2011). This online data compendium is updated biennially and includes data tables on scientists and engineers with disabilities and graduate students in science and engineering with disabilities, relying on the SED and the NPSAS as data sources. While the data tables focus only on science and engineering, they provide more detailed data on disabilities than other reports based on the SED and do so in a more user-friendly format than the NPSAS.

Although the figures vary between the two sources, the SED and the NPSAS provide some information on the participation of students with disabilities in graduate education. Regardless of the data source, the scope of that participation highlights the importance of addressing the varied and unique barriers that students with disabilities face in their pathways to and through graduate school.

By Nathan E. Bell, Director, Research and Policy Analysis

References

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). 2009. 2007-08 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:08). Dataset.

National Science Foundation. 2010. Doctorate Recipients from U.S. Universities: 2009. Retrieved from www.nsf.gov/statistics/nsf11306/nsf11306.pdf

National Science Foundation. 2011. Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering: 2011. Retrieved from www.nsf.gov/statistics/wmpd/

U.S. Census Bureau. 2011a. “R1801. Percent of People 5 to 20 Years Old With a Disability.” Retrieved from http://factfinder.census.gov

U.S. Census Bureau. 2011b. “R1802. Percent of People 21 to 64 Years Old With a Disability.” Retrieved from http://factfinder.census.gov

(Reprinted from the August/September 2011 issue of the CGS Communicator)

While the primary focus of the CGS International Graduate Admissions Survey is on the participation of international students in U.S. graduate education, this year’s Phase II survey also asked institutions to respond to two questions about prospective U.S. citizen and permanent resident graduate students. In the first question, institutions were asked to provide the number of applications for graduate programs received from U.S. citizens and permanent residents for fall 2010 and fall 2011. In the second question, institutions were asked to provide the number of offers of admission for graduate programs granted to U.S. citizens and permanent residents for fall 2010 and fall 2011, as of June 5th or the same data each year. This article presents an analysis of the findings from these two questions.

The survey population for the 2011 CGS International Graduate Admissions Survey, Phase II: Final Applications and Initial Offers of Admission consisted of all 493 U.S. colleges and universities that were members of CGS as of May 2011. A link to the survey instrument was e-mailed to the graduate dean (or equivalent) at each member institution on June 8, 2011 and responses were collected electronically through July 31, 2011.

Applications from U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

A total of 234 institutions provided data on applications from U.S. citizens and permanent residents for fall 2010 and fall 2011 (Council of Graduate Schools, 2011). Of those institutions, 170 (73%) were public institutions, 63 (27%) were private, not-for-profit institutions, and one was a private, for-profit institution. By Carnegie classification, 171 (73%) of the respondents were doctoral institutions, 50 (21%) were master’s-focused institutions, and 13 (6%) were institutions classified as baccalaureate or specialized. By geographic region, 65 (28%) of the responding institutions are located in the Midwest, 43 (18%) in the Northeast, 40 (17%) in the West, and 86 (37%) in the South. Respondents to the question included 71 of the 100 largest institutions in terms of the number of graduate degrees awarded to U.S. citizens and permanent residents (National Science Foundation, 2011). The 234 responding institutions conferred about 40% of all graduate degrees awarded to U.S. citizens and permanent residents in the United States in 2008-09.

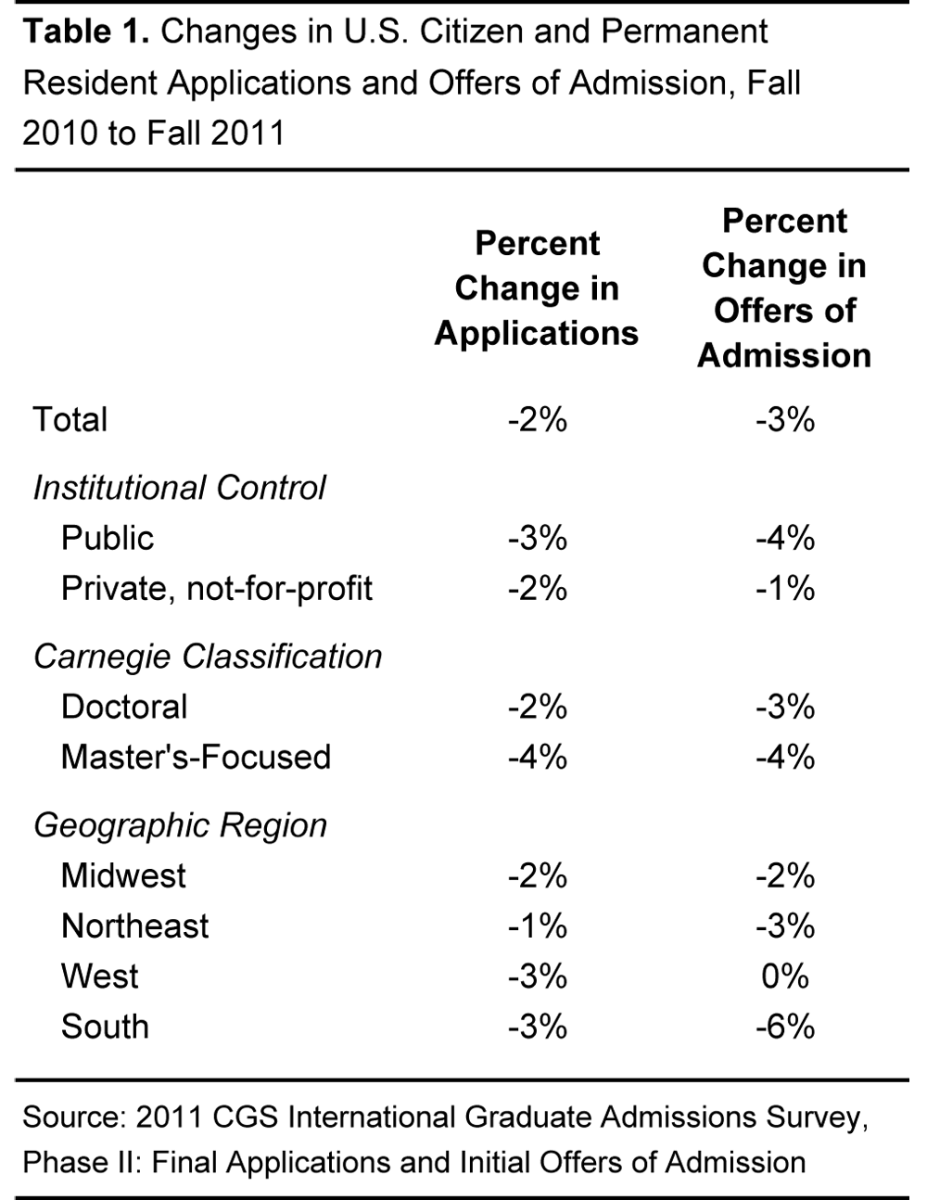

Overall, applications from U.S. citizens and permanent residents fell 2% between fall 2010 and fall 2011 (see Table 1). Of the 234 institutions that provided data for both 2010 and 2011, 125 (53%) reported a decrease in applications from U.S. citizens and permanent residents for fall 2011, with an average decline of 8% at these institutions. At the 108 institutions (46%) reporting an increase, the average gain in applications from U.S. citizens and permanent residents was 6%. One institution reported no change in applications from U.S. citizens and permanent residents between 2010 and 2011.

The change in applications from U.S. citizens and permanent residents varied minimally by the number of graduate degrees awarded. At the 71 responding institutions that are among the 100 largest in terms of the total number of graduate degrees awarded to U.S. citizens and permanent residents, applications from U.S. citizens and permanent residents fell 3%, while at the 163 responding institutions outside the largest 100, applications from U.S. citizens and permanent residents fell 2%.

Applications from U.S. citizens and permanent residents fell 3% in fall 2011 at public institutions, slightly more than the 2% drop at private, not-for-profit institutions. Doctoral institutions reported a 2% decrease in applications from U.S. citizens and permanent residents, while master’s-focused institutions reported a 4% drop. Decreases in applications from U.S. citizens and permanent residents occurred in all four geographic regions of the United States, with the largest decreases in institutions located in the South and the West (both -3%), followed by the Midwest (-2%) and the Northeast (-1%).

Offers of Admission to U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

A total of 230 institutions provided data on offers of admission to U.S. citizens and permanent residents for fall 2010 and fall 2011 (Council of Graduate Schools, 2011). Of those institutions, 167 (73%) were public institutions, 62 (27%) were private, not-for-profit institutions, and one was a private, for-profit institution. By Carnegie classification, 169 (73%) of the respondents were doctoral institutions, 49 (21%) were master’s-focused institutions, and 12 (5%) were institutions classified as baccalaureate or specialized. By geographic region, 63 (27%) of the responding institutions are located in the Midwest, 42 (18%) in the Northeast, 39 (17%) in the West, and 86 (37%) in the South. Respondents to the question included 71 of the 100 largest institutions in terms of the number of graduate degrees awarded to U.S. citizens and permanent residents (National Science Foundation, 2011).

Overall, offers of admission to U.S. citizens and permanent residents fell 3% between fall 2010 and fall 2011 (see Table 1). Of the 230 institutions that provided data for both 2010 and 2011, 132 (57%) reported a decrease in offers of admission to U.S. citizens and permanent residents for fall 2011, with an average decline of 11% at these institutions. At the 98 institutions (43%) reporting an increase, the average gain in offers of admission to U.S. citizens and permanent residents was 9%.

The decrease in offers of admission was greater at institutions awarding smaller numbers of graduate degrees to U.S. citizens and permanent residents. At the 71 responding institutions that are among the 100 largest in terms of the total number of graduate degrees awarded to U.S. citizens and permanent residents, offers of admission to U.S. citizens and permanent residents fell 1%, while at the 159 responding institutions outside the largest 100, offers of admission to U.S. citizens and permanent residents fell 7%.

Offers of admission to U.S. citizens and permanent residents fell 4% in fall 2011 at public institutions, a larger decrease than the 1% drop at private, not-for-profit institutions. Doctoral institutions reported a 3% decrease in offers of admission to U.S. citizens and permanent residents, similar to the 4% drop at master’s-focused institutions. Offers of admission to U.S. citizens and permanent residents remained flat at institutions located in the West, and declined in the South (-6%), the Northeast (-3%), and the Midwest (-2%).

Discussion

The findings for U.S. citizens and permanent residents in the Phase II survey are in stark contrast to those for international students. The 2% decline in applications from U.S. citizens and permanent residents compares with an 11% increase in international applications for fall 2011 (Bell, 2011). Similarly, the 3% decline in offers of admission to U.S. citizens and permanent residents compares with an 11% increase in international offers of admission for fall 2011.

While there are different trends for domestic and international students, the data do not necessarily indicate that international students are being admitted in lieu of domestic students. Since the increase in international offers of admission (+11%) mirrors the increase in international applications (+11%), and the decrease in domestic offers of admission (-3%) mirrors the decrease in domestic applications (-2%), the changes in offers of admission may simply be a reflection of the changes that occurred in application volumes.

Two important caveats need to be considered in the interpretation of these data. First, the figures for U.S. citizens and permanent residents may not be as final as those for international students. Some colleges and universities continue to admit students throughout the summer, particularly for master’s-level programs. Given the time it takes to secure a visa, international students are less likely to apply at this late stage than are domestic students, so it is possible that the final figures for U.S. citizens and permanent residents might differ from those presented here. Second, it is possible that the data may not be representative of all institutions in the United States. While the survey respondents award about 40% of all graduate degrees to U.S. citizens and permanent residents, trends may differ at institutions that did not respond to the survey. This non-response bias is especially important to consider since the data on U.S. citizens and permanent residents were collected as part of the CGS International Graduate Admissions Survey. Institutions with small numbers of international students—particularly master’s-focused institutions—may have been less likely to respond to the survey.

The survey is not able to shed light on the exact cause of the declines in U.S. citizen and permanent resident applications and offers of admission, but several factors, including the continued uncertain national economy, declining state budgets and their effect on financial aid packages at public institutions, the weak job market, the availability of student loans, and many other factors, are likely at play. What the survey does reveal is the need to continue to track the application and enrollment patterns of domestic students and the importance of providing the pathways and support needed for these students to successfully enter graduate education.

By Nathan E. Bell, Director, Research and Policy Analysis

References:

Bell, N. 2011. Findings from the 2011 CGS International Graduate Admissions Survey, Phase II: Final Applications and Initial Offers of Admission. Washington, DC: Council of Graduate Schools.

Council of Graduate Schools. 2011. 2011 CGS International Graduate Admissions Survey, Phase II: Final Applications and Initial Offers of Admission. Dataset.

National Science Foundation. 2011. WebCASPAR Integrated Science and Engineering Resources Data System. Accessed August 11, 2011.